Speaking of Fluency: Language Skills in High Demand

Kenia Avendano-Garro is a teaching assistant at the University of Wisconsin. She teaches beginning Japanese.

“People were lined up for hours,” says Kenia Avendano-Garro ’10, who was the sole American and only female in her Japanese university’s manga club (Japanese comics). When she heard about the club’s part in an annual fall cultural festival, she volunteered to help. On the day, she drew manga-style portraits of people who came to their booth. After the festival, she went with the other volunteers to a “drinking club,” or nomihôdai, to celebrate.

For Avendano, the evening marked her entrée into a culture that can often remain closed to foreigners.

“That was the first time I went out socially with Japanese students,” she says. “In Japanese culture, it is often considered inappropriate/impolite to converse casually with a foreigner. One time, a Japanese woman on the street asked me where I had bought a sticker she saw I had. I answered her—in Japanese—but she noticed my Western face, apologized quickly, and left.”

Avendano had no idea her high school interest in manga and anime (Japanese animated stories) would someday lead her to studying abroad in Japan. But as her affinity for the culture grew, so did her curiosity about the language. She started teaching herself Japanese. Working before the availability of Google Translate, she used resources at-hand then: slow Internet, language dictionaries, and anime films.

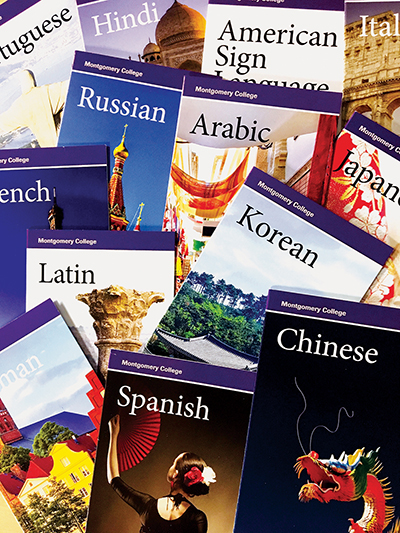

At MC, where students can choose from more than 13 languages, Avendano dabbled in Korean and Chinese. At the University of Maryland, she majored in Japanese language and literature. When a professor there encouraged her to study abroad and vied for financial aid for her to attend Keio University in Tokyo for nearly a year, she seized the opportunity.

At MC, where students can choose from more than 13 languages, Avendano dabbled in Korean and Chinese. At the University of Maryland, she majored in Japanese language and literature. When a professor there encouraged her to study abroad and vied for financial aid for her to attend Keio University in Tokyo for nearly a year, she seized the opportunity.

During her first semester in Japan, Avendano did her best to adapt. Not only was it her first time living overseas, it was her first experience living away from her Rockville home. The dorm in Yokohama where she lived with other Keio students was 17 miles south of Tokyo, so she rode the speedy but notoriously crowded trains back and forth to campus.

“I found out that the mid-day trains to Shibuya—one of Tokyo’s busiest railway stations—were less crowded, so I adjusted my student train pass to travel at those times. Our dorm had a communal kitchen, but I learned that I could buy traditional cooked meals at the local convenience store. I was interacting in the language every day, which was very important in becoming fluent.”

Looking back, Avendano says staying in Japan for nearly a year was better than a single semester. Since she was navigating Japan alone, she spent the first semester learning a new way of life, learning to communicate, “studying too much,” and making Japanese friends. By the second part of her stay, she was able to enjoy the experience a little more.

In addition to the manga club, she joined a conversation club outside the university, where volunteers spoke with her and checked her homework.

“Japanese people don’t usually correct your grammar. And I definitely made my mistakes,” Avendano says. “The conversation club was very helpful.” She was also learning the written Japanese forms: hiragana, katakana, and some kanji. Hiragana, the phonetic system and katakana, the system used for foreign words, are now common alongside kanji, the traditional characters that originated in China.

After her second trip to Japan, as a University of Wisconsin graduate student, Avendano achieved her goal of fluency. She spent eleven months at the Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Studies, or IUC, in Yokohama. There, she was among mostly American graduate students.

After her second trip to Japan, as a University of Wisconsin graduate student, Avendano achieved her goal of fluency. She spent eleven months at the Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Studies, or IUC, in Yokohama. There, she was among mostly American graduate students.

“I interacted in the language every day and had instruction there in my area of specialization—so I was able to practice reading and discussing Japanese literature. My skills are close to a native speaker now.”

Sharon Fechter, instructional dean of humanities, says Avendano’s path to fluency—immersion—is powerful. Fechter started as a Spanish professor at MC in 1999, and later chaired the College’s World Languages and Philosophy Department. She herself achieved fluency after studying abroad.

“After high school, I went to Spain to study before college,” she says. “I double-majored in college: Spanish and speech and drama, but stuck with Spanish. I did my doctoral work in Spain, but my PhD is from NYU.”

Avendano and Fechter are among less than 1 percent of US adults who achieve fluency from language programs studied in a classroom. Of the US Census Bureau’s estimated 65 million US residents ages five and older who speak a language other than English at home, most acquired those language skills at home, rather than in school. Referred to as heritage speakers, they have a working knowledge of a second language acquired from family and cultural associations.

Until recent years, the common thought in US populations has been that since English is the common language of commerce and diplomacy around the world, there is less need than other countries to learn languages. But shifting demographics and an increasingly global economy are influencing lawmakers and educators to look more closely at the benefits of teaching a language other than English to more Americans.

According to a 2015 Kiplinger’s article, “Best Foreign Languages for Your Career,” nearly a half-million job postings in the US specifically requested foreign-language proficiency. The article, which circulated on social media, also stated hiring managers look favorably on bilingual job candidates. Japanese was number four on its list of “10 best foreign languages for your career” after Chinese (number one), German (number two), and Portuguese (number three). Remaining in the top 10 were—in order—Spanish, Korean, French, Arabic, Hindi, and Russian.

A growing body of evidence for increasing language skills in the United States was supplied more recently by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Commission on Language Learning. In its 2017 report, “America’s Languages: Investing in Language Education for the 21st Century,” the commission outlines ways that language learning influences economic growth, cultural diplomacy, and the productivity of future generations.

In its key findings, the report states: “the United States needs more people to speak languages other than English to remain competitive in business, research, and international relations. Workers are continuously needed to provide social and legal services for a changing population.”

“Students like Kenia are finding career options with language skills,” says Fechter. “There is a high need regardless of college major. In engineering and science, candidates that can bring language skills are more desirable. And there are so many career opportunities in our area with federal agencies that employ thousands of contractors with language skills.”

Avendano, now in her third year of a six-year PhD program, has already benefited financially from her Japanese language skills. She has translated scripts for a Japanese TV drama series, cell phone games, and anime. She has an ongoing teaching assistant position at the University of Wisconsin, teaching beginning Japanese to undergraduates. Last summer she taught Japanese at a language-immersion youth camp in Minnesota.

Whereas Avendano struggled to find resources just a few years ago, language learners today have apps for computers and smartphones that allow them to learn and practice. But for students seeking fluency—and all the benefits it brings—financial challenges prevent them from exploring their bilingual pathways.

“We are pursuing grants that will allow more of our community college students to travel abroad for language acquisition,” Fechter says. “We are already so fortunate the College supports language learning. Not only do we have a robust program, but also we are adding languages and growing our Japanese, Korean, and Russian programs. When you consider the population of Montgomery County, it makes a lot of sense to support language programs.”

Help Wanted: Critical Languages Required

The US Department of State has identified these as critical languages, non-Western European languages important to US national security (December 2016). It offers a variety of scholarships and programs for college students who wish to study them, including language and cultural immersion programs overseas.

The US Department of State has identified these as critical languages, non-Western European languages important to US national security (December 2016). It offers a variety of scholarships and programs for college students who wish to study them, including language and cultural immersion programs overseas.

| Arabic | Azerbaijani | Bangla | Chinese | Hindi | Indonesian | Japanese |

| Korean | Persian | Punjabi | Russian | Swahili | Turkish | Urdu |

[Source: CLSscholarship.org]

Popular Language Apps for Smartphones and Computers

Lingua.ly

Quizlet

Memrise

Duolingo

GraphoGame

[Source: America’s Languages: Investing in Language Education for the 21st Century, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Commission on Language Learning report, 2017]

—Diane Bosser

Photography by Brent Nicastro

Illustration by Clint Wu

Hello,

My name is Toyoko Leonard. I am working at University Southern Maine in Portland Maine as a Nursing Lab Specialist. My passion and 2nd interest is always global communication with college students or anyone who wants to learn about Japanese language and culture n the United States. I am searching any opportunity to teach Japanese in my area but so far not many students are found to learn in Japanese language in past year. I am posting to see if anyone knows students who want to learn Japanese language/culture from me. I have taught in University of Maine Orono, also taught many other students (age 12-80) outside of college in past, some lived in Japan with Jet Program. If you would like to contact me for any information of people want to learn Japanese language and culture please contact me at sayoyuka2@yahoo.com or call/text 207-699-9729. I am open to everyone who wants to learn.