An Interview with John Rolfe Gardiner

An Interview with John Rolfe Gardiner

by Ellen Sullivan

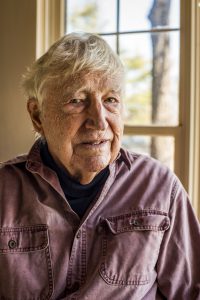

John Rolfe Gardiner spoke to Potomac Review from his home in rural Loudon County, Virginia, 50 miles northwest of Washington, DC, at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The handsome, white-haired writer tapped on the desk he built for his study, creating a staccato rhythm behind our conversation, edited here for clarity. In November, Gardiner celebrated his 87th birthday with the news that Bellevue Literary Press will be publishing his fourth short story collection, North of Ordinary, in which “Tree Men” appears.

PR Congratulations on your new collection. You say it feels like a rebirth.

JRG Well, the New Yorker was taking my stories, but they closed their doors to me some twenty years ago. I had a story collection at Atheneum, then two books at Knopf. When they didn’t want the next book, I went to Counterpoint which published two, Double Stitch, a novel, and my favorite, The Magellan House collection. For some years I haven’t had a publisher, and my agent can’t be expected to mess with short stories because there’s so little return. Whatever success I had with short stories I placed on my own. Then to have them discovered by this wonderful publisher of quality books is sort of like a rebirth and up from the ashes. It’s very difficult for anybody to get published these days. There are thousands of people wanting to be writers or poets and success may depend on someone you know who will suggest you to an editor but in this case, it was a cold submission and the pleasure of unexpected discovery.

PR You’ve published sixteen stories in The New Yorker and six novels and now another success. But you’ve spoken about feeling like an imposter.

JRG I think I always wanted to be a writer but I certainly never supposed that I could. There’s always the fear that you’re going to be seen to be something of a fraud or that you are in fact a fraud. Each fiction begins as a mystery – where is it going, will anybody want to read it – and there’s always an editor looking over your shoulder askance at the manuscript and smiling. I don’t know any writers who call themselves “authors,” that have the pretension to refer to themselves that way. They’d say “I’m a writer” or “I’m a wannabe writer” unless they are so fluent and so gifted – say, John Updike, who was able to talk about himself as an author in the third person. There are only a few of those in the world, I think. If you’re me you look at yourself with the humility of a lost soul when you face the blank page.

PR So what gives you the nerve to write?

JRG Stubbornness. Admiration for good writing. I want to try it in spite of the penalties that may follow.

PR The imposter is a character you return to in your stories. In “Tree Men” the nameless narrator doesn’t really have the skills to be on the crew.

JRG The idea came from my experience working for a swimming pool contractor in rural Virginia when I was in high school. I had family backing and the men I was working with had nothing but the health of their own bodies to fall back on so there could be a natural resentment to me as a student and as somebody who was more fortunate in resources. They had a certain way of welcoming me in their own lingo and they saw that I would work hard but they also knew that I was separate. I could leave at any time, and they depended on it all their lives so that was my perspective in looking at the tree men.

I was on my way to my local village one day and I saw a tree climber working up in a locust tree next to the highway. I stopped and got out of my car and incredibly he was making warbling noises like a bird, whistling beautifully in a way that I’d never heard before. At first, I thought it was a bird and then I realized that he was doing this and I could hear him when the chain saw was off. That became the Embry character. When I was thinking about the joy he found up in the air, the joyous sounds of whistling in contrast with the misfortunes of his life, it made me think of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” which ends with those beautiful lines, “So little cause for caroling, Of such ecstatic sound.” That was the way the thing sort of came together.

PR Was the Hardy poem sitting in your memory or had you recently come across it?

JRG In the Army on the midnight shift I memorized some poetry, in particular Yeats. But the Hardy lines were a gift of a liberal arts education. In high school, we had to be able to identify quotes from dozens of poems. As an English student in college, poetry seemed the be-all and end-all of creative writing. In ninth grade our text defined poetry as “the best words in their best order” and prose as just words in their best order. Pretty silly. And other things such as “What is an Epigram, a dwarfish whole, its body brevity and wit its soul.” And the definition of a novel, still hanging around seventy years later.

PR What was that?

JRG “The extended story of a group of individualized characters made to come to life in a normal background whose characters interact on one another toward a specific outcome. The ultimate test of a novel is in its character drawing. It’s said that in a good novel the outcome is not only possible but probable, and in a great novel, it is inevitable.” Learned by rote, and almost Victorian in its pat certainties. Maybe useful as a reminder of classical expectations.

PR You attended Sidwell Friends High School in Washington, DC, then earned a BA in English from Amherst. That’s your formal education, but you say all writers depend on earlier writers to teach them.

JRG There’s a lot about other writers and stuff you pick up along the way. Margot Livesey’s The Hidden Machinery is full of wise advice. And she shares her early mistakes – how too much research and irrelevant detail got in her way.

Flannery O’Connor said don’t go rummaging around too much in your characters’ heads.

Fitzgerald said, start with an individual and maybe you’ll create a type – start with a type and you’ve created nothing at all.

Grace Paley said she didn’t like doorknob turners. She was famous for being able to switch from one generation to another or one character to another without an apparent transition, you just pick it up from the context of what you’re reading.

The wonderful story writer Berry Morgan said, “If there’s a problem with a manuscript, write about it.”

I’m sure all writers have a list of other writers who have taught them.

PR Why short stories?

JRG Well, they can have just as much impact as a novel. Deborah Eisenberg once made the comment that the novel and short story both share the same fixed costs – situation, plot, character, revelation. You need all the same elements, but you can’t be as loose and chatty getting them on the page.

I don’t know how to tell you what makes a good story. Nobody can even define a short story or a poem for that matter. I think Housman said I can no more define a poem than a terrier can define a rat, but I think we both recognize the object by the symptoms it provokes in us. With the short story, the best you can say is it’s shorter than a novel. How much shorter? You decide.

If there’s anything you learn as you go along it’s that you want to make your characters seem organic — the things that are said organic to the situation. You can recognize stories in which the author’s cleverness is placed in the character without much relevance, trying to be interesting but the reader sees that all these observations have nothing to do with the truth of the character they’re talking about.

There aren’t any final rules because every one of them has an exception. They always say show don’t tell but there can be marvelous creative narrative that advances a plot and reveals character. You don’t want to hear the machinery of the plot clanking along with the writer telling you what happens next and next with no character or dialogue in sight. Fitzgerald observed that action is character.

PR What kind of writing do you like?

JRG I want there to be rules about reality. I guess I’m not a fan of magical realism. I want there to be life as I understand it or experience it, not as something that could happen in a world that doesn’t exist. Have you ever read the collected short stories of V.S. Pritchett? He’s so great at knowing different voices, different argots, at understanding situation and writing organically within it. Try reading the Complete Stories of V.S. Pritchett. Read “Passing the Ball,” read “The Diver,” read “The Camberwell Beauty” – all of them. It’s sort of my bible of short stories.

PR You also find inspiration from your home county in Northern Virginia, a setting you return to in many of your stories.

JRG Northern Virginia makes a generous backdrop to write against. It’s where I grew up and returned to after college, the Army, and some years in New York writing for a trade journal and in D.C. working as an editor. I started writing stories about a rural village like the one I lived in with its nosiness around a corner store and the hypocrisies and delinquencies that give a place its peculiarity.

Anybody living here has seen the physical transformation of a county quadrupling in population. Then there’s been another transformation, even more intrusive – the steam clouds rising over data centers, a reminder of the cyber cloud hanging over everyone and the lost privacy of surveillance capitalism.

PR You’ve written lyrics about that –

Turns out he’s been part

Of a storm up on high,

Already been sold

To the cloud in the sky…

A blizzard of yes and no,

All about him…

JRG Those were lyrics about a rodeo rider for Furnace Mountain, a roots music band based here in Loudon County.

PR Your lyrics from another song speak to the history of Northern Virginia, a history that seeps into your stories.

In the heart of the heart of Virginia,

Before blue and gray mingled blood,

On the ridge that leads down into Georgia

Above the Potomac in flood,

A story past knowing or telling

Is blazed in the bark of the pines,

Where speckled trout swim in the highlands,

Where redbud and dogwood make shrines.

In the heart of the heart of Virginia

By soldiers’ bones tangled in vine

The fox and his vixen take refuge

In caves carved by water and lime.

Below on the Piedmont’s rich farmland,

The corn tassels gold in the sun,

Two rivers run through Harper’s Ferry,

Where federals shouldered their guns.

In the heart of the heart of Virginia

A healing still waits for its time,

Long mem’ry hangs over the red clay

Where creeper and green ivy climb.

By the Great Falls where white water tumbles

On down to the Chesapeake Bay,

The spirit of Jefferson walks with John Brown,

Still looking for something to say.

Your novels are grounded in American history, too. The slaving industry in pre-Revolutionary War Rhode Island, labor disputes in a Tennessee mining town in the 1890s, a World War I family drama unfolding in letters between France and New York, a Philadelphia orphanage after World War I, and Northern Virginia village life after World War II. Someone could teach an American history course using your novels as touchstones. Preparing for the publication of your new story collection, are you still finding time to write stories?

JRG Yes, but it’s easier to putter around in my wood shop. I’ve been working on some chairs after the style of Sam Maloof.

–End–