That Henry Greenb aum spoke November 16th at the Germantown campus of Montgomery College recounting his experiences living in the ghetto, enduring death marches as well as slave labor in concentration camps after the loss of his mother and five of his eight siblings in Poland during the Holocaust—while the Syrian city of Aleppo, home to some of the world’s oldest and most historic communities, where half a million people have been killed in the last six years, including a significant part of the Armenian population, descendants of the refugees of the first genocide of the 20th century, was burning—would be a notable occurrence on any campus, yet it was but one among several recent examples of the college’s commitment to the study of genocide.

aum spoke November 16th at the Germantown campus of Montgomery College recounting his experiences living in the ghetto, enduring death marches as well as slave labor in concentration camps after the loss of his mother and five of his eight siblings in Poland during the Holocaust—while the Syrian city of Aleppo, home to some of the world’s oldest and most historic communities, where half a million people have been killed in the last six years, including a significant part of the Armenian population, descendants of the refugees of the first genocide of the 20th century, was burning—would be a notable occurrence on any campus, yet it was but one among several recent examples of the college’s commitment to the study of genocide.

One week later, another Holocaust survivor, Manny Mandel, spoke to students in an upper-level literature class. In fact, every year the college offers a Literature of the Holocaust class, English 248, and in 2008, with the support of the Arts and Humanities Council of Montgomery County, the college created a photographic art exhibit entitled Portraits of Life, displaying portraits of Holocaust survivors along with their narratives that, upon examination and reflection, lend themselves to classroom lessons and discussions about discrimination, prejudice, racism and intolerance and which has grown to include education programming for use by secondary school teachers, a traveling photo exhibition and a speakers program, now in its tenth year.

And in June, in association with the Smithsonian, the college hosted a symposium on teaching the Holocaust with digital primary source materials, instructing faculty from all over the world how to teach with museum resources, using the Smithsonian’s collection, as well as those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Library of Congress, to add a visual dimension to discussion in the classroom about the language of genocide—that is, the deployment of euphemisms like purification, evacuation, resettlement and mercy death. In educational settings, precision of language is, of course, itself a value and may help to teach that the Holocaust and events like the carnage in Aleppo, the once and current cynosure of the world’s homicidal indifference and, looking back 100 years, the dismissal of the Armenian Genocide, are not inevitable.

While some of the cultural producers of the Holocaust survived—Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi, for example—the perpetrators of the first genocide of the 20th century made plans so that their Armenian cultural counterparts would not. On the night the Armenian Genocide began, April 24, 1915, two hundred and fifty Armenian poets, writers and intellectuals were rounded up and, except for the sixteen who managed to escape, were slaughtered, the first knot in the noose of the 1.5 million of their countrymen who were to follow, a fact which lent urgency and particular relevance to the inherited and ancestral mission of the winner of this year’s Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, Peter Balakian, whose book, Ozone Journal employs long lines, drawn- and drowned-out thoughts, as well as collages of clauses to piece together a theory of atrocity that searches for a connecting thread in the language, not only of the victims, but of the perpetrators as well, a thread that would link the victimization of Armenians in Aleppo and in the Syrian desert to the victims of the massacres in, among other places, Poland, Rwanda and Sudan, to the victims and victimizers in Aleppo, Syria today, and beyond that to the existential crisis that all humanity faces in the thinning of the ozone layer, in climate change, if that thread be only the futility of garnering interest in doing anything about them.

October is the month of literary prizes, and while the literary world (and significant parts of the non-literary world) was still debating the merits and demerits of Bob Dylan’s award—all we know for sure is that he sent prepared remarks, did not attend the Nobel ceremony, citing a scheduling conflict, and invoked William Shakespeare whom, he imagined, would have been busy with more quotidian obligations, the New Jersey-born Balakian (who, oddly enough, has written an essay entitled “Bob Dylan in Suburbia”) was on hand, along with Viet Thanh Nguyen, the prize winner in fiction for his novel, The Sympathizer, and Lin-Manuel Miranda, who won the prize in drama for his musical, Hamilton, at the 100th anniversary ceremony of the Pulitzer Prize, held at Columbia University, in New York.

The Pulitzer committee cites Balakian’s Ozone Journal for “poems that bear witness to the old losses and tragedies that undergird a global age of danger and uncertainty,” a description that hints at Balakian’s particular responsibility to his ancestors; for while genocide always involves an assault on a people’s cultural producers, those, that is, who create the webs of binding significance and common meaning, the Armenian Genocide began with the planned and wholesale eradication of the very soul of its culture’s symbolizing identity, and, therefore, the responsibility to resurrect the reality of that time has fallen, for the Armenians, on writers like Balakian, two generations removed from the event that Hitler, when confronted with the enormity of his planned crime, dismissed with, “Who r emembers the Armenians?”

emembers the Armenians?”

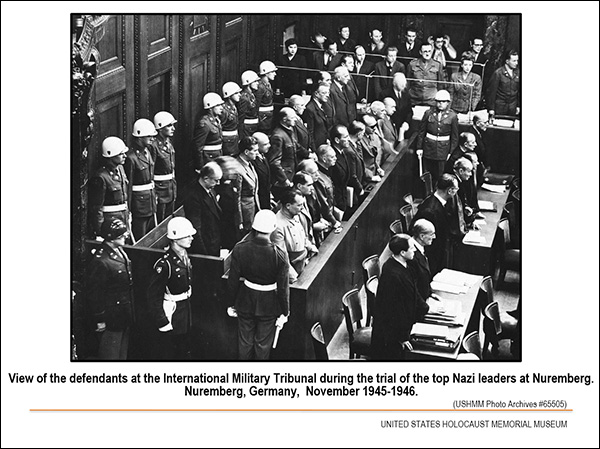

Indeed it was only during the Nuremberg trials, where some Nazi perpetrators were held to account, that a new legal concept was brought to the world’s attention—genocide, coined by the legal scholar, Raphael Lemkin, in 1944, who, after studying the attempted extermination of the Armenians, argued for the denotation of a special crime to describe a systematic campaign to exterminate an entire ethnic group. The Armenian Genocide, therefore, became, in legal parlance, the first genocide of the 20th century, but began, uniquely, with the eradication of the very people who could write about it, and exists, even today, under a persistent campaign that denies the truth of its having occurred.

Balakian, therefore, has a triple burden, which lends him, because of its weight, both an unwieldy inheritance, but also a focus and an observational superpower to write about the perils of our day that, in one way or another, are either being dismissed, denied or played down. If he is forced by circumstances to be the symbol maker of his time and place, he has become that symbol maker because the slaughter of innocents that is happening today happened in some of the same places where his ancestors lived and died. Because of this, he is also uniquely equipped to channel the voices of the victims of the slaughterhouses in places like Bosnia, Rwanda and Darfur, which bridge the two time periods, while, at the same time, connecting these events to a planet that is in peril, and, in the process, uncovering an Atlantis of connection in people and places driven insane by torture and grief.

On Facebook one can read posts from Syrians today that could have echoed from a century before: “My soul is leaving my body. Aleppo, my life, my life.” As a poet, Balakian carries the very improbability of this shared identity over time as a source of his metaphorical power, that is, his ability to make equally improbable connections, and that, along with his triple burden and, therefore, triple focus, bestows rights upon the individual—the subject of the violence in his poems—if only in retrospect, and also bestows power against the impersonal forces arrayed against him because to cultural genocide, Balakian is able, thanks, in a manner of speaking, to the culture’s victimization, link ecological “genocide,” and, by way of the burning ozone layer, and the warming world, create a study of “othering,” and through it, link the disregard of the humanity of a people through violent expulsion and indifference, or claims of ignorance, to the ranking of the relative value of people by the blasting off of mountaintops and the manufacture of geographies that create sacrifice zones that dot the planet.

Balakian’s poems are said to conjure the inchoate drift of modern consciousness as it confronts these seemingly disparate realities. The title poem, “Ozone Journal,” begins with the narrator waking up “to CFCs humming out of coils” and describes a long drive from Aleppo to Der Zor that Balakian took with a TV crew from CBS’ 60 Minutes for a story on the Armenian Genocide—a story specifically intended to film the excavation of remains of Armenian skeletons in Der Zor where a half a million of his ancestors died.

2

All day I was digging Armenian bones out of the Syrian desert

with a TV crew that kept ducking the Mukhabarat

who trailed us in jeeps and at night joined us

The speaker of this poem journeys over land, but also through his memories of the 1980s—when a cousin, and best friend, was dying of AIDS, and there was a dawning awareness of the devastating implications of climate change, both realities providing a spiritual Baedeker through which to “explain” a travelogue of the Syrian desert, which, by definition, makes it a travelogue of historical layering without documentary evidence. Balakian’s sometimes Whitmanesque long lines interweave time periods and cultures, the living and the dead, in the kind of collage that doesn’t offer logical coherence but surrounds the reader with the voices of history’s victims as well as the piling up, through history, of the blind eyes to their slaughter. In this context, it is important to remember that neither Turkey nor the United States officially recognize the reality of the Armenian Genocide—which may lead some readers to think that the oft-quoted “never forget” is in fact, while honored, no longer operative, even ridiculous, in the face of so much official denial. Perhaps the deniers are assuming it is for the best—after all, given what followed the Holocaust in places like Cambodia, Rwanda and, now, Syria, it is perhaps a form of magical thinking to think that remembering previous massacres does anything to stop new ones from occurring. One assumes, however, that this fact does not imply implicit acceptance of white nationalist groups in this country who deny the Holocaust and believe white identity has become endangered and under threat in an era of diversity and multiculturalism. But even so, the reader may be left wondering about the implications of being able to pick and choose which genocides upon which to confer acceptance.

The Armenian Genocide is remembered because, in 1933, the Austrian novelist, Franz Werfel, chose the Biblical number forty to highlight, not so much the tribulations of the Armenians, but through them, the fate he foresaw for the Jews. His best-selling novel, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, conceived in Damascus, Syria, chronicled the story of his hero Gabriel Bagradian’s participation in the mountaintop resistance against superior Turkish armies. The Nazis burned the book because Werfel’s warning was clear, at least, to them: The Armenian tragedy was a prologue.

The word Musa “stands for Moses,” Vartan Gregorian points out in the preface to the English translation published in 2012, and even though the real story was that the Armenians were able to hold out for more than fifty days, Werfel’s “forty days” implied that the Armenian tragedy, which had almost been forgotten, might soon play itself out again, but this time with a different band of victims. The parallels between Turkish Nationalism and National Socialism proved potent; in fact, the underground fighters in the ghettos of Germany often carried Werfel’s book with them. Mordechai Tenenbaum, a resistance fighter in the Bialystock ghetto in Poland, wrote, “only one thing remains for us: to organize collective resistance in the ghetto, at any cost, to let the ghetto be our Musa Dagh.” According to Samuel Gringauz, a principal in the Kovno Ghetto in Lithuania, the resistance fighters passed Werfel’s book from hand to hand. Thanks to Werfel’s mountaintop gorilla army of Armenian villagers, who held out against Turkish forces on the peak of Musa Dagh, the fact of the Armenian Genocide began to spread around the world. One can only speculate, in this light, that the United States’ official denial of the Armenian Genocide does not, given the carnage in Aleppo today, imply that we are better off forgetting than remembering, or that the next time a monument is raised, it would be better, as a Northern Irish writer once suggested, to erect a monument to amnesia and forget where we put it.

15

Speeding by al-Raqqah, appearing, disappearing—

the idea of Babylon, Assyria, Sumer:

an abstraction of sun on water—toward Margadeh—smell of sand storm rising—

caves appearing, disappearing into stone huts of light.

In 1991, to counter, among other things, such a willful forgetting, a very small Armenian church was consecrated in Der Zor, and though it, too, was recently destroyed by Islamic militants, it was built shortly after the worldwide heads of the Armenian Church issued a joint statement announcing plans to study the canonization of the martyrs of the Armenian Genocide. Pilgrims retraced the journey through the desert to worship there, and on April 23, 2015, one day before the 100th anniversary of the start of the Armenian Genocide, its 1.5 million victims were formally recognized as martyrs and canonized as saints of the Armenian Church, marking the day after which the Church no longer offered requiem prayers for them but instead asked for their intercession with God.

If ever a people seemed, in their history, to understand the theologian’s Karl Barth’s conception of a God perfectly independent of human phenomenon—“the God who stood at the end of some human way—even of this way— would not be God”—it is the Armenians. As the British diplomat and colonial administrator Charles Eliot wrote, “few races have produced more martyrs in ancient as well as modern times, or come in contact with more persecutors.” Thirteen hundred years earlier, a letter to the Persian king, after the battle of Avarayr, in 451 A.D, convinced the Persians that the Armenians, though conquerable, would never give up their faith: “Even if the immortals themselves came to our aid, it would be impossible to establish Mazdaiism in Armenia.” Perhaps, it might be said, the killing fields of Der Zor are the nearest visual icon one can find of this completely transcendent vision of God, a visual icon, paradoxically, in its—to use the theologian’s Rudolf Bultmann’s term—“totalier aliter,” or “wholly other” quality, of God’s manifest radiance.

Whether or not it is odd that 100 years later, in the same places, millions of people face persistent threats of starvation and torture, the same Hobson’s choices people confronted in the Armenian Genocide, of “death either way”—mortal danger, that is, in staying, mortal danger in fleeing—both situations continue to draw the attention of poets. The greatest living poet of the Arab world (and a perpetual contender for the Nobel Prize), the 86-year old pseudonymous Syrian, Adonis, confronts and addresses official erasure, just as a public letter and prose poem written in 1990, during the 75th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, by the pseudonymous Armenian-American poet, Zareh, (which began “I stood at Musa Dagh and read the destiny of my people”) addressed United States’ official denial of the events of 1915.

While the first Christian saints were martyrs—witnesses, that is, by definition, “to the truth of Jesus’ promise”—the debate about the poetry of witness began in the United States in 1993, with the anthology Against Forgetting, compiled by Carolyn Forché, and to which Peter Balakian, though not a native Armenian speaker, provided collaborative translations of Armenian poets. The book brought focus to a discussion about the relationship between poetry and history, and included poets like Pasternak, Akhmatova, Prévert, Sachs, and the Armenian poet Vahan Tekeyan. Forché offered a list of the different kinds of responses to what she called “political extremity.” But for Balakian, poetry details what happens to an individual in the context of what happens to a culture and a nation. For him, the lyric poem, therefore, must be capable, as he argues in his collection of essays, Vise and Shadow, published in 2015, of “ingesting violence,” and documenting, somewhere and somehow in its complicated mechanism, the “tremors of trauma or manifestations of traumatic memory.” For Balakian, the poem must be able to embody the pain of a person and people confronting collective violence.

The great Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, who wrote a cycle of poems dedicated to Armenia, said that “the Armenian language cannot be worn out: its boots are stone,” so it may seem ironic that it falls on Balakian, who grew up in the northern reaches of the Mid-Atlantic, in suburban Tenafly, New Jersey, where he was a year-round sports fanatic—“halfback one season, point guard another, shortstop another”—to be the voice of its genocide. Byron, too, loved the Armenian language, having studied it on the island of San Lazarro, in Venice, when his mind, he said, “wanted something craggy to break upon,” but it is, in fact, sadly fitting that a non-native speaker be its voice, as such are the ironies when the entire corps of a peoples’ cultural producers are slated for death during the first days of a planned race-wide extermination. To name only a few of the greatest poets and writers executed at the outset, Daniel Varoujan (1884-1915), Adam Yarjanian (pseudonym “Siamanto” 1878-1915), Krikor Zohrab (1861-1915), and Ruben Sevag (1885-1915) had established European, if not worldwide, reputations by the time of their executions, and while Balakian’s great-uncle, the bishop, Grigoris Balakian, was one of the sixteen who would survive a forced march through the Syrian desert, in the direction of Der Zor, and whose memoir Armenian Golgotha is one of the few eyewitness accounts of the Armenian Genocide, the younger Balakian is its poet. And while he is an Armenian poet, he is also an American poet in a poetry scene where there has been a jettisoning of literary history, in lieu of the adaptation of personal and idiosyncratic family history, and therefore, Balakian, with the obliteration of both his personal family history and his people’s literary history has been left to fend, as a poet, for himself. Perhaps that, too, is part of the paradox of his power.

Even as a professor of Humanities at Colgate University, Balakian faces the marginalization of the humanities in American education along with its corporatization and with it, too, a co-opting of the cultural producers who it employs. Before the 54-part title poem, an earlier poem, “Hart Crane in LA, 1927,” reconstructs a conference where English department job candidates go for their job interviews:

We sat in leather chairs

around cocktail tables and the candidatescame and went with badges on their jackets, proud and scared,

full of knowledge and uncertainty.Everyone was animated as the conversation

drifted toward an idea of the idea of the text.

In this playful sendup of academic conversation about poetry, a colleague points out that they are in the same hotel where Hart Crane once rode into “LA’s great pink vacuum of / sunsets and spewed Rimbaud out on the Boulevard” and later:

Another colleague said you couldn’t understand Crane’s big poem

without context, the other said you couldn’t understand

context without the poem.

Soon, however, Balakian is on the journey back in time, crossing the Syrian desert to his own youth in the 1980s and drawing from sources as disparate as Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, John Cage’s 45’ for a Speaker and Susan Sontag’s AIDS and its Metaphors when writing about his cousin, dying of AIDS in a hospital. Balakian always casts the personal in historical context and the pursuit of personal meaning inside the pursuit of cultural meaning. The 24th section of the title poem ends hinting at the irony that many Turkish villagers have never heard of Armenians, transforming the harsh reality behind the Armenian-American painter Arshile Gorky’s observation that “the great art of our people lies hidden in ruins and amid the daily life of remote villages” into the gossamer of poetry.

24

On Sundays I came to the hospital with a café au lait and choreg—

David was all memory as if a little Madeleine were floating in tea:

outside of a jazz club in Beyoglu, Turkey—he told me:

Alan (the love of my life) was ranting (why there, why then?)

about the wall that came down

at Stonewall, before we all/and then/and how/

the Humpty Dumpty faggot cops, handcuffed women,

Van Ronk and company too.Fairies weren’t supposed to fight back;

someone doused the bar with lighter fluid—

the street was Jackson Pollack smashed,

pay phones toilets jukebox cigarette machines—we hung our peacock-embellished texts

on the graffiti-ripped plaster of Christopher Streetspectral emanations rose off the curb.

And here we were standing under the Turkish street light,

charred lamb in the air;

we chugged our scotch andand back we went inside the club with

a couple of Kurdish guysand later near dawn set out to find

the wall on the Bosphoruswhere our family house once was.

Reviewers have pointed out how “Ozone Journal” manages to juxtapose, in the manner of collage, seeming disparities—how it recounts in one place, for example, the police in Aleppo keeping an eye on Balakian as well as the Armenian priest who walks with him one night, and who is missing by noon the next day, while interweaving recollection of a guy eating pizza who “put[s] it casually” that he was in shop class in December 1988, “shaving a hammer in a drill press,” when the floor began to drop—a reference to the earthquake that killed 25,000 Armenians and from which sectors of the country still haven’t recovered—and somehow makes artistic, if not theodicic sense of them. “Ozone Journal” also recounts what it was like for the poet to be close to the border with Turkey, and nearing Ani, once the “City of 1,001 Churches,” the Florence of Armenia, as a boy asks him “why Armenia didn’t have a covenant with God like the Jews did.” This the Ani Byron thought was encircled by the Garden of Eden, this the Ani for whom Balakian named his daughter, this the Ani, now converted into a city of 1,001 laundromats, where there is little trace left of its millennia of Armenian presence.

In the last poem of his Pulitzer Prize-winning volume, “Home,” Balakian is still driving, this time in his own car, each line alternating between places like Anatolia and places like Syracuse, New York, where he is returning home to teach, the images melting into each other, the exile always leaving, and always finding home, and always and everywhere seeing home in places of genocide like Ivory Coast, Sarajevo and Syria, individual and ancestral homes, but always, also, mediated in the trancelike drift of consciousness, ruminating on killings and their horrific consequences one moment, on genocide, and on the language of genocide itself, another, the poet always allowing for perspectives to mash together and make their own music, ingesting the violence, and so somehow simultaneously transforming the atrocities into the poetry on the page, and perhaps, therefore, transforming the person reading the page. Perhaps it is too much to ask that the reader burn with the same intensity, but if the existential crisis we face as a people and a planet today concerns the burning ozone layer, then it, too, like the Armenian Genocide, is in some quarters being denied and requires some sort of argument. And while it is probably an impossible task to create a cohesive narrative out of the different layers of meaning and history when they are mashed up with their own denial, “Home” ends with a final merging and, at the same time, during Hurricane Sandy, the unmistakable submerging of a city which, ironically, in a connected age, with more images of contemporary atrocity than ever before, has very little power to burn through the indifference:

Driving Route 20 to Syracuse past pastures of cows and falling silos

you feel the desert stillness near the refineries at the Syrian border.

Walking in fog on Mecox Bay, the long lines of squawking birds on shore,

you’re walking along Flinders Street Station, the flaring yellow stone and walls

of windows where your uncle landed after he fled a Turkish prison.You walked all day along the Yarra, crossing the sculptural bridges with their

twisting steel,the hollow sound of the didgeridoo like the flutes of Anatolia.

One road is paved with coins, another with razor blades and ripped condoms.

Walking the boardwalk in January past Altantic City Hall, the rusted Deco

ticket sign, the waves black into white,you smell the grill cevapi in the Bascarsija of Sarajevo,

and that street took you to the Jewish cemetery where the weeds grew over

the slabs and a mausoleum stood intact.There was a trail of carnelian you followed in the Muslim quarter of Jerusalem

and picking up those stones now, you’re walking in the salt marsh on the

potato fields,the day undercut the flatness of the sky, the wide view of the Atlantic, the

cold spray.Your uncle stashed silk and linen, lace and silver in a suitcase on a ship that

docked not far from here; the ship moved in and out of port for years, and

your uncle kept comingand going, from Melbourne to London to Kolkata and back, never returning to

the Armenian village near the Black Sea.The topaz ring you passed on in a silver shop in Aleppo appeared on Lexington

off 65th;the shop owner, a young guy from Ivory Coast, shrugged when you told him you

had seen itbefore; the shuffled dust of that street fills your throat and you remember how a

slew ofcoins poured out of your pocket like a slinky near the ruined castle now a disco in

Thessaloniki where a young girl was stabbed under the strobe lights—lights that

lit thesky that was the iridescent eye of a peacock in Larnaca at noon, when you walked

into thechurch where Lazarus had come home to die and you forgot that Lazarus died

because the story was in one of your uncle’s books that were wrapped in

newspaper in a suitcase andstashed under the seat of an old Ford, and when he got to the border

he left the car and walked the rest of the way, and when he passed the apartment

on 116th and Broadway—where your father grew up (though it’s a dorm now)—

that suitcase is buried in a closet under clothes, and when you walk past the

security guardat the big glass entrance door, you’re walking through wet grass, clouds

clumped on a hillside, a subway station sliding into water.