When I last visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I started…

Professor Monica Mische, Professor of English

In my English 101 class this fall, I approached this year’s Smithsonian Faculty Fellowship theme in a rather indirect way. Instead of exploring social justice issues from political or historical perspectives, I asked students to delve deeply into their own lives, to twine narrative threads to create meaning, and, ultimately, to connect their stories to other people’s so that they might view themselves as beautiful, strong, unique but also as part of a broader fabric of humanity that is, like them, capable of growth and change.

I have followed this general outline for several years, but this term, thanks to the fellowship, I have enriched my course with new elements, including visual analysis and a trip to the National Portrait Gallery. For several years, my keystone assignment has been for students to craft a four-chapter autobiographical novella about a transformative journey they have experienced. The journey can be physical, emotional, or spiritual, often touching on all three. Students have written about geographical journeys they’ve taken (as tourists, immigrants, or refugees). They’ve recounted spiritual awakenings, embracing sexual and gender identities, the joys of parenthood, the pursuit of dreams. They’ve described struggles with addiction, family dysfunction, poverty, abuse, profound loss, and grief.

This year, the pain and isolation of Covid infiltrated many of the stories. Students described how the pandemic damaged their mental and physical health, interrupted schoolwork, affected their family’s livelihood, and inflicted trauma. But they’ve also described resulting acts of kindness, unexpected strength, newfound paths—an emergence from darkness. As they craft their novellas, they attend to word choice, sensory description, setting, dialogue, and suspense. And they consider how the experience impacted them: what they have lost, gained, and come to understand as a result of their experience.

Once students have written about their own journeys, our next step is to immerse ourselves in the journeys of other people. Students love reading stories of other students, and each semester I make available an online archive of novellas by my past students and invite current students to contribute to the collection. After perusing multiple novellas, students select one to examine in depth. I tell them that their job is to explore the writing with such care that they imaginatively enter into the story and live it alongside the author. They then compose an essay in which they summarize their classmate’s story and illuminate its significance and meaning. The assignment pushes them to practice close reading techniques and to discover embedded themes – themes that by their very definition take readers beyond the personal to the universal.

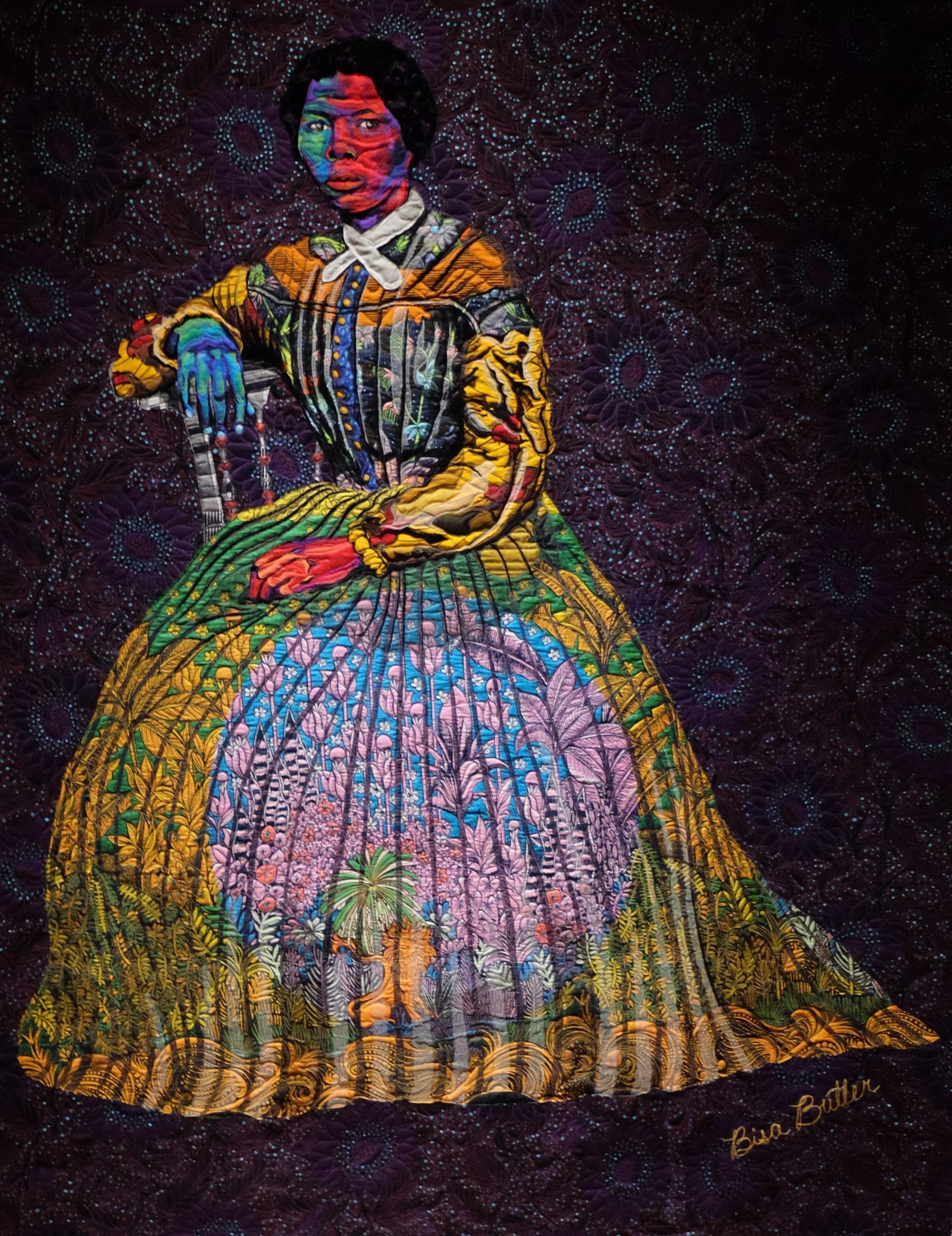

My time in the Smithsonian cohort has helped me realize that while written stories wield great power, images, too, touch the mind and heart, and in notably different ways. Through facial expression, physical stance, gesture, foreground, background, tone, and color, artfully rendered portraits of human experience, though frozen in time, transport us to vast and sundry worlds and thereby, in a language beyond words, build insight and empathy. Thus, I’ve introduced a new course component involving visual immersion and analysis.

Luckily for us, two remarkable exhibits were on display this fall at the National Portrait Gallery: The Outwin 2022 and Kinship, and these became for us pivotal learning tools. Before our visit, we practiced analyzing portraits with “learning to look” strategies gleaned from the Smithsonian’s Reading Portraiture Guide for Educators. By contemplating what we see, think, and wonder, and by jumping, imaginatively, into a portrait, we uncover the “human story”. New worlds open up, deepening our encounters with art, with stories, and with each other.

Held every three years, The Outwin Portraiture Competition showcases diverse, contemporary artists in a stunning variety of media, subjects, and themes and is notable for its representations of everyday American life. Many finalists of this year’s competition feature struggles faced amid the pandemic, illuminating the heroism of frontline workers, the isolation of life in quarantine, and interpersonal bonds experienced even in difficult times.

For example, students were drawn to Alison Elizabeth Taylor’s Anthony Cuts Hair under the Bridge 2020. This gorgeous wood-laminate portrait celebrates a young stylist who, when his shop was shuttered during the pandemic, styled hair for donations on a busy New York underpass in order to raise money for Black Lives Matter. The piece reminded students of the despair so many felt during quarantine, but also of the incredible acts of generosity and innovation our shared crisis engendered.

For example, students were drawn to Alison Elizabeth Taylor’s Anthony Cuts Hair under the Bridge 2020. This gorgeous wood-laminate portrait celebrates a young stylist who, when his shop was shuttered during the pandemic, styled hair for donations on a busy New York underpass in order to raise money for Black Lives Matter. The piece reminded students of the despair so many felt during quarantine, but also of the incredible acts of generosity and innovation our shared crisis engendered.

Students also felt captivated by Elsa Maria Melendez’ Milk. Dazzling in scale, the sculpted fabric depicts a young woman draped in white and carrying a bull, representing the strength of the Puerto Rican women who demanded government response to the spike in women murdered during the pandemic. After viewing this impressive piece, students reflected on gender-based violence in their own communities as well as an increased willingness to speak out against these horrors.

Rigoberto A. Gonzalez’s Refugees Crossing the Border Wall into South Texas resonated with the many MC students whose families, in emigrating to the U.S., have withstood grave risk and sacrifice. Gonzalez portrays the immigrant family with a luminous dignity that reminded students of classical nativity paintings. However, “clues” such as a discarded face mask and a crumpled newspaper (announcing Trump Impeached) place the scene squarely in Covid times.

The Kinship exhibit likewise proved compelling. Through painting, collage, photography, paper-mache, cloth, wood, and dance, eight artists share their vision of human connectedness, each with a dedicated room, bringing viewers into an intimate space that feels deeply personal but also relays universal themes.

Students were struck by LaToya Ruby Frazier’s ethnography of the Flint, Michigan water crisis. Some students’ families had likewise experienced unsafe water and sanitation, as had Frazier herself. However, even for those who had never suffered such scarcity, empathy abounded. A photograph of a mother brushing her daughter’s teeth with bottled water felt especially poignant; learning about the mother’s activism on behalf of her daughter and her community proved inspiring.

Students felt moved, too, by photographic portraits from Thomas Holton’s twenty-year documentary project The Lams of Ludlow Street. The Lams, despite austere living conditions and the eventual dissolution of their marriage, showered Holton with remarkable hospitality, revealing that kinship involves more than blood ties, that the people we spend time with and open our homes to can truly become family.

And Sedrick Huckaby’s intensely textured, emotionally evocative paintings and sculptures proved a meditative salve for all of us who have mourned the loss of loved ones. His exhibit room felt like, as one student put it, a sacred place – where the dead and the living reunite. Amen, Connections, and Gone But Not Forgotten help us, irrespective of age or race or circumstance, feel the sanctity of life, inspiring us to see and remember human love and light.

And Sedrick Huckaby’s intensely textured, emotionally evocative paintings and sculptures proved a meditative salve for all of us who have mourned the loss of loved ones. His exhibit room felt like, as one student put it, a sacred place – where the dead and the living reunite. Amen, Connections, and Gone But Not Forgotten help us, irrespective of age or race or circumstance, feel the sanctity of life, inspiring us to see and remember human love and light.

After exploring these stirring exhibits, students composed an essay for which they analyzed how artistic elements stand out in a specific portrait to create meaning; how this selected portrait resonates with them; and, more universally, what it says about human life, the human condition.

Our closing assignment was an essay in which students compared and contrasted their own journey with the journey depicted in a classmate’s novella or (as a new option this semester) to an experience relayed in a portrait from the National Gallery. Though walking separate paths from their subjects, students identified common challenges, setbacks, comebacks and yearnings, and reflected upon shared lessons and themes, recognizing the compassion, care, and courage that lead to transformative growth.

Blending analysis with interpretation and personal response, the portrait project invited students to engage with art actively (with a discerning eye, an imaginative mind, an open heart) and to recognize the essential nobility of human love and striving. Indeed, the Smithsonian faculty fellowship, like the Paul Peck Institute which sponsors it, promotes an inquiry that truly is humanistic. It shines a light on hardship, injustice, sorrow, despair, but also commemorates the human capacity to love and become positive change agents in a complex, interconnected world.

This Post Has 0 Comments