By Professor Tiffany Banks On Tuesday, September 30th , students from my COMM 108: Foundations…

By Brandon Wallace, Professor, Education

In 2019, I traveled to Ghana for the Year of Return—a charge and call for people throughout the African diaspora, within the United States, to visit Ghana, one of the largest, former enslavement trading ports in the world. The call insisted that African Americans should return to the country that possibly could have been the place of their origin, to reestablish a sense of belonging, and even seek Ghanaian citizenship. I decided to visit the Gold Coast. On my way there, I visited Saltpond, a town and the capital of the Mfantsiman Municipal District in the Central Region of South Ghana and traveled to one of the lesser-known areas of the international slave trade, Elmina Castle.

As I looked over the horizon of where I was, I could see dozens of boats just docked on the shores. I asked my tour guide to explain to me the reason people were not working to retrieve the fish, which, in my limited estimation, reasoned to be the gainful employment for those Ghanaians to sustain themselves in both food and trading-income. My driver, Kwesi, explained to me that they were not fishing because there were not enough fish in that region. After hundreds of years of depending on that source of nutrition and income, global warming had ravished their most important resource. I was devastated.

This realization of the nontraditional construct of reciprocal teaching that I experienced from Kwesi, and several others who I encountered in Ghana, built the empathy that I needed to appreciate global warming and the ability for me to connect with people from an entirely different background than I possessed. When I first began my Smithsonian journey, I thought I was going to, through the Smithsonian Faculty Fellowship, study global warming through the lens of cultural responsiveness and relevancy in Ghana. I was confident that the work I was going to be engaged in was going to help me and my colleagues think about culturally responsive teaching and learning, especially here at Montgomery College’s School of Education. I was so excited to ensure that I created a new, innovative learning experience for all my students, particularly in the Education 101 offering at MC. However, the global pandemic left me with an inability to make the connections and convergences I needed to truly create a project with fidelity and accountability.

In short, my connections and networks in Ghana simply could not move forward with our initial plan, i.e., to focus on the fisheries of Ghana to enhance student understanding of the role of global agriculture, internal industry, and education. The connections I made were immediately tasked to focus solely on figuring out the pandemic. Of course, while I was disappointed, I immediately understood. I was left slightly despondent and lost because my initial plan was so immediately cancelled and, thinking and looking back to how uncertain the pandemic was, and at times still is, I knew it was the right thing to do, but I also wanted to make sure that my students got the quality education and experience I once envisioned. I was in limbo—uncertain about what my new, improved plan would be.

I knew I wanted to do a global project, and I was left thinking what I should do. Who should I contact? In short, Philippa Rappoport, Manager of Community Engagement Programs Manager of the Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access, and I were able to speak about global ideas and thoughts. After about ten minutes of conversing over Google Hangouts, we found a commonality proving just how small the world was. Phillipa shared with me information about a man with the last name of Thomas from the District of Columbia Public Schools System, who had a daughter who was a teacher in United Arab Emirates. Phillipa shared with me stories about how this Mr. Thomas was, like me, an urban education professional who spent much of his time in DC—changing the way the District of Columbia did STEM education. I asked Phillipa about Mr. Thomas a bit more, and I collected all the information I needed to exclaim to Phillipa that I knew Mr. Thomas’s daughter, Talibah! I shared with Phillipa that I met Talibah years ago when I traveled the UAE in 2006, and I even shared that Talibah helped me with a small interview project that I did a couple of years back. Phillipa and I were able to make the connections from Washington, DC, to Montgomery County, to UAE and back—proving, again, just how small the world truly is!

After speaking to Phillipa a bit more, I mentioned that I knew quite a few teachers over in the UAE—having traveled there and having spoken at a few local schools in Abu Dhabi. I created a brand-new idea and bridged the gap between what I was unable to do in Ghana to an even better project in UAE—filling my project idea with even more opportunities for my students to connect what they were learning in coursework to what they were going to be soon asked to produce. I reinvented my project from Ghana and ended up in the UAE—proposing a global, collaborative project between Montgomery College, the Smithsonian Institution, and Time to Teach, a consultant with ADEC Abu Dubai Education Council. I knew I could not go at this project alone, so I drew in more experienced individuals from across the country, i.e., Jennifer Bowden, Director of Education, World Affairs Council of Dallas/Fort Worth; Rebecca Fenton, Curator, Smithsonian Folklife Festival Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage; and Zenani Fogg, Education Consultant for Time to Teach ADEC Abu Dhabi Education Council. The human resources listed above all helped me to organize and facilitate possible filming or other documentation with Smithsonian staff member in Abu Dhabi and to connect Montgomery College students with young learners and principals in UAE to ensure that the videos are utilized.

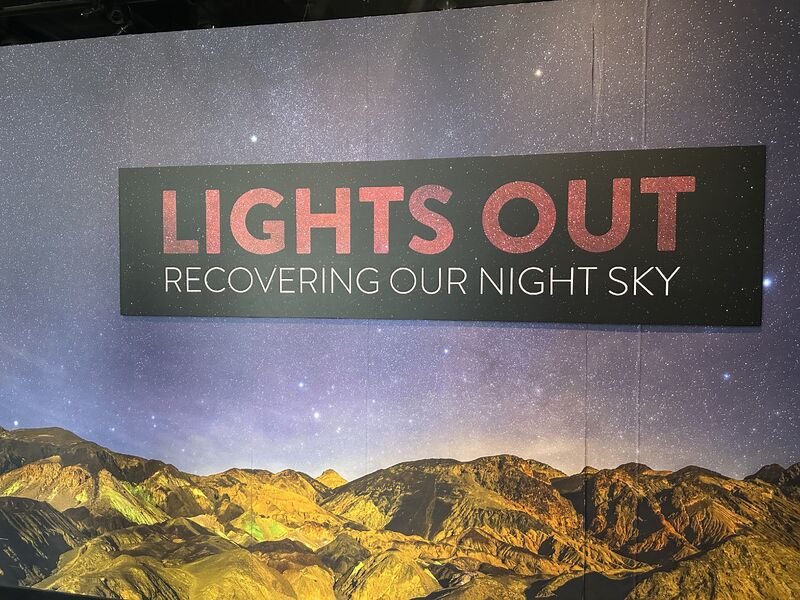

I explained to my Montgomery College student that their fall Education 101 class was going to be different from any other class they would be taking—even possibly over their entire college career. In short, I told the students that our class was supported by the Smithsonian Institute, and they would be engaged in a global enterprise, essentially interfacing with students in the United Arab Emirates. The project, I explained, would remotely take us to the Smithsonian’s myriad of resources throughout the entire semester, and they would all be developing a small part of a lesson plan to engage students in the United Arab Emirates—the part of the lesson that grabs the attention of learners and introduces them to a developed lesson. Our theme, keeping our efforts aligned to the theme of my fellowship, was global warming and climate change in the United Arab Emirate (UAE). Additionally, I mentioned that we would be working closely with officials from the Smithsonian, educational partners from UAE, as well as a host of other supports from Montgomery College.

I explained to my students they would have to develop a lesson plan opener and deliver it as a recording to the class and ultimately to the Smithsonian Institute, as well as students in the United Arab Emirates. Of course, I had to teach them about the constructs of a lesson plan, e.g., warm-up or a do-now that teachers employ to grab the interest and attention of their students. I did not feel comfortable with them creating an entire lesson just yet, but, particularly from EDUC 101, it was the most developmentally appropriate assignment to think of for their level of experience in education. I told the students they had to be sure to make their lesson plan openers exciting, interesting, entertaining, informing, and engaging. My students were able to choose any grade levels they wishes based upon available plans shared with us from Jennifer Bowden—mentioned above. They students were amazed and excited!

Now, there is a fully developed Open Education Resource/ Z-Education (EDUC) 101 Course—developed completely through Blackboard that embeds the project that was given to my students this past fall; there is an amazing repository of student-centered, student-work, i.g., culturally responsive and relevant lesson plans w/ video vignette compilations, and, best of all, a prudently-created Smithsonian-supported internship designed specifically for Montgomery College students to create educational activities for the National Mall, that has been offered for my students in the Education 101 that occurred in the fall of 2020. One of the hidden curricula components I wanted to prove to myself is that there was a way to, even in the midst of a global pandemic, still be able to globally connect with students around the world to enhance the sharing of teaching and learning. My students were able to take what they learned from me in Education 101 and share it with students in The UAE—with masks on, social distance, and an excitement that was unparalleled.

You crafted a design that will stay with your students and their community of learners forever. You have them starting at the right spot (the beginning) to create an opening (grabber, hook, anticipatory set) with a “developmentally appropriate assignment to think of for their level of experience in education.”

Never again will any of them be satisfied with “yesterday we were on page 86. Turn now to page 87.”

Beautiful and awe-inspiring narrative. Brandon, you capture the essence of innovation at the heart of teaching, dismantling the status quo and raising the standard.

“I explained to my Montgomery College student that their fall Education 101 class was going to be different from any other class they would be taking—even possibly over their entire college career.” Your students are privileged to have your intellectual curiosity shape their introduction to and stewardship in the field. Kudos to you on regrouping in the midst of a global crisis, for not skipping a beat, and for creating an environment where creating cross-cultural connections is the norm and not the exception.