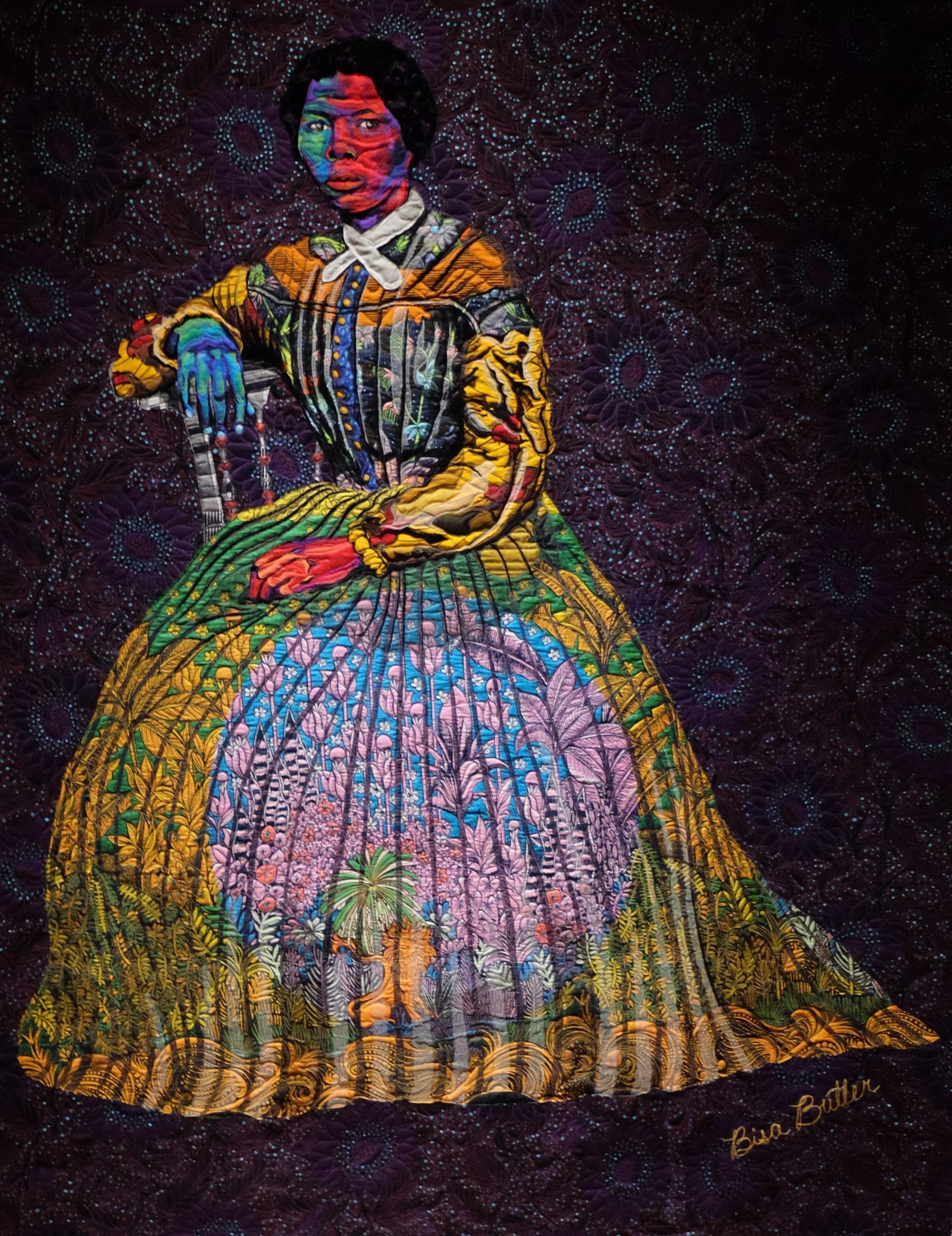

When I last visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I started…

by Dr. Alison Melley, Psychology

“I always thought the American History museum was boring.”

“I was really surprised at how many different people are represented in this exhibit.”

“I cannot believe this is on display here.”

My class visits to the museum were a success. Students had a scavenger hunt to complete, and they did this with a typical amount of enthusiasm. They are currently working on their assignments – “How Did I Become the Person That I am Becoming?” for my General Psychology students at  Montgomery College (MC) and George Mason University (GMU), “An Examination of My Cultural Identity as a Future Psychotherapist,” for my Clinical Psychology students at GMU, and “An Examination of My Cultural Identity as a Future College Professor,” for my Teaching Practicum students at GMU.

Montgomery College (MC) and George Mason University (GMU), “An Examination of My Cultural Identity as a Future Psychotherapist,” for my Clinical Psychology students at GMU, and “An Examination of My Cultural Identity as a Future College Professor,” for my Teaching Practicum students at GMU.

This is the culmination of an own ongoing examination of my own cultural identity development and the evolution of my identity as an educator. I am looking forward to seeing the projects my students produce, but right now I am just overwhelmingly grateful for this space to explore ideas, and for my students’ openness to this experience.

Growing up, my world was small. My community consisted of almost entirely white Catholic school families living in suburbia. My town was quite segregated – a black city and a white suburb, with a few “other” nationalities sprinkled in. The family dinner table, however, formed four daughters who were curious about the rest of the world, open to new ideas, and passionate about social justice.

When I went to a public high school, where students were bussed from the city, I made new friends and experienced a bit more of “the world,” only beginning to realize my privileged positioning. Some of my teammates from the city could not show up for games or track meets unless our coach picked them up, along with their little siblings. Sometimes I rode with him, so we all piled into his van, some on the floor, some in the “way back,” and made memories. Unfortunately, while this was a “benefit” of busing for me (I ran on some amazing relay teams and made friends outside of my bubble) – I wonder if the girls would have benefited more from programs that focused on improving the schools in the neighborhoods they lived in, rather than being removed from their homes.

When I went to a public high school, where students were bussed from the city, I made new friends and experienced a bit more of “the world,” only beginning to realize my privileged positioning. Some of my teammates from the city could not show up for games or track meets unless our coach picked them up, along with their little siblings. Sometimes I rode with him, so we all piled into his van, some on the floor, some in the “way back,” and made memories. Unfortunately, while this was a “benefit” of busing for me (I ran on some amazing relay teams and made friends outside of my bubble) – I wonder if the girls would have benefited more from programs that focused on improving the schools in the neighborhoods they lived in, rather than being removed from their homes.

I never really felt like I belonged with these teammates, and did not feel fully accepted by them – I felt their anger and resentment, but wasn’t sure what it was all about. My naïveté didn’t

allow for me to understand. An open mind can only be “open” so much without the experience to go with it.

Fast forward to my first “real” job, working in foster care with a primarily minority population. Again, I went in with my eyes and mind open, but completely naive. In hindsight, I am sure that my “privileged self” committed micro-aggressions every day. I wanted to help and serve, but did not understand why I struggled to connect. I was rejected outright because I was a “white woman,” and I didn’t know how to ask the questions that I needed to ask in order to move forward.

Although I continued to try to find ways to right wrongs and change minds, I did not have the tools or insight to be as effective as I wanted to be. When I began teaching at MC almost eight years ago, my previous experience at being rejected as a helper haunted me. I was confronted by the fact that I had no idea how to best serve our globally diverse population of students. I could teach about psychology, sure – but being an educator is also about relationships – and I was frozen by the perception that I was not able to form these relationships. Ensuring feelings of competence and belonging in students is incredibly difficult if you don’t feel competent yourself.

A refreshing change came when I started discussing these issues in my educational psychology classes. I found lived experience in the phrase “I learn more from my students than they learn from me.” The students welcomed a classroom environment that was open to discussions of privilege, marginalization, and cultural identity. The privilege of being let into their world was at times overwhelming but the discussions were so much richer.

Fast forward again to the Smithsonian Faculty Fellowship, which helped give structure to my idea that educators who examine their own “stuff,” and what they bring to the classroom, can more readily bring down the barriers to connection with students. I can create a “safe space” in my classrooms for all students to learn, and then I can build this into a “brave space” for them to grow.

At the Many Voices One Nation exhibit at the National Museum of the American History, students were moved by the display of items left behind in the desert and the piece of border fencing, as well as the overall diversity in the exhibit. The excitement was in the details, however. Vjosa was fascinated by the bios of African American students in a 1941 yearbook. Lara shared with me her experiences learning about American history growing up in Northern Virginia schools. Alex was found excitedly taking pictures of a Mexican cake that he eats with his own family. Ariella worked hard to get a picture of the map on the wall behind the border

fencing. She told us about living in south Texas as a little girl, crossing back and forth over the border on a regular basis. Shea talked about his culture growing up in Appalachia, and his transition to the D.C. area. Mishely was so pleased to see Bolivian dancers in the video collage, reminders of her childhood.

I felt a bit unprepared going into the first visit. Life is a bit of a whirlwind lately, and I showed up to the exhibit much like my students – a little harried, not quite sure what to expect or how to get started. In hindsight, I believe that my lack of expectation allowed me to enjoy observing my students experiencing the exhibit for the first time themselves. When the actor came by singing, asking us to go to the student sit-in next door at the Greensboro lunch counter, we did so happily. I was even allowed to act as protestor – I sat at the counter while students and other museum visitors crowded around behind me. While this was a powerful and somber experience, there was an air of fun and adventure when we moved back to Many Voices – and when I sent them off with suggestions of other exhibits to explore, they seemed to have a spring in their step that wasn’t there in the beginning. I did too.

I felt a bit unprepared going into the first visit. Life is a bit of a whirlwind lately, and I showed up to the exhibit much like my students – a little harried, not quite sure what to expect or how to get started. In hindsight, I believe that my lack of expectation allowed me to enjoy observing my students experiencing the exhibit for the first time themselves. When the actor came by singing, asking us to go to the student sit-in next door at the Greensboro lunch counter, we did so happily. I was even allowed to act as protestor – I sat at the counter while students and other museum visitors crowded around behind me. While this was a powerful and somber experience, there was an air of fun and adventure when we moved back to Many Voices – and when I sent them off with suggestions of other exhibits to explore, they seemed to have a spring in their step that wasn’t there in the beginning. I did too.

This Post Has 0 Comments