Setting the Right PACE in First-Year English Composition: A Student Success Initiative

By Professor Elizabeth M. Benton, Chair, Rockville English Department and Professor Rebecca Eggenschwiler, Collegewide Coordinator, PACE Program

The Montgomery College English and Reading Department launched an innovative pilot program in spring 2012, called Program for the Advancement to College English (PACE), to change the trajectory of developmental student completion in college-level English courses. Since the program’s inception, it has served more than 1,100 students – 500 developmental students and approximately 650 college-ready students – in five semesters. In the fall 2015 semester a record number of students will be impacted by this program: 450 first-semester Montgomery College students will be supported in 24 sections of ENGL 101A PACE.

The Montgomery College English and Reading Department launched an innovative pilot program in spring 2012, called Program for the Advancement to College English (PACE), to change the trajectory of developmental student completion in college-level English courses. Since the program’s inception, it has served more than 1,100 students – 500 developmental students and approximately 650 college-ready students – in five semesters. In the fall 2015 semester a record number of students will be impacted by this program: 450 first-semester Montgomery College students will be supported in 24 sections of ENGL 101A PACE.

What is PACE?

The Montgomery College Advancement to College English program (ACE) was initiated in 2012 to increase access to credit-level English courses at the College. Led by English faculty and chaired by Marcia Bronstein, a faculty  committee designed a pedagogical shift in the English classroom: slightly smaller class sizes, an in-class tutor, and student success teaching strategies provide the foundation for what is now called the Program for the Advancement to College English (PACE).

committee designed a pedagogical shift in the English classroom: slightly smaller class sizes, an in-class tutor, and student success teaching strategies provide the foundation for what is now called the Program for the Advancement to College English (PACE).

The PACE model promotes a specific classroom environment and support structure for eligible students: students must enroll through the English and Reading Department for scheduling and monitoring purposes; students in each ENGL 101A PACE class consist of 10 college-ready students and eight PACE or developmental students; and each class receives an in-class tutor who assists for 15 hours of the semester.

What is the impact of PACE?

Data collected by English and reading faculty members indicate that approximately 75 percent of the PACE and non-PACE students earn an A, B, or C in the ENGL 101A course.[1] Compared with data gathered by the Montgomery College Office of Institutional Research and Analysis (OIRA), the faculty-collected data indicate that PACE students are keeping up with or exceeding the traditional ENGL 101 student grade achievement.[2] In addition, recent data show that PACE students are moving on to ENGL 102/3 in high numbers. Of the successful students in PACE in fall 2013, more than 80 percent attempted ENGL 102/3 in the next semester and 71 percent of those students passed ENGL 102/3.[3]

Data collected by English and reading faculty members indicate that approximately 75 percent of the PACE and non-PACE students earn an A, B, or C in the ENGL 101A course.[1] Compared with data gathered by the Montgomery College Office of Institutional Research and Analysis (OIRA), the faculty-collected data indicate that PACE students are keeping up with or exceeding the traditional ENGL 101 student grade achievement.[2] In addition, recent data show that PACE students are moving on to ENGL 102/3 in high numbers. Of the successful students in PACE in fall 2013, more than 80 percent attempted ENGL 102/3 in the next semester and 71 percent of those students passed ENGL 102/3.[3]

Based on early calculations, the PACE program is having a positive effect on Montgomery College’s developmental student population, always with room for improvement, of course. A welcome yet surprising byproduct of the PACE program is a meaningful impact on faculty engagement. In this important era of community college reform, student success and faculty engagement are much needed. [4] The ENGL 101A PACE program continues to thrive as a student success innovation and a positive influence on the faculty experience at Montgomery College.

Why did the PACE program begin?

In the past few years, community colleges have targeted resources toward studying student success, specifically developmental student success.[5] One study of community college students in Maryland found that 17,599 students needed at least one developmental class at entry into community college.[6] Of those students, approximately 38 percent of the developmental students completed the developmental program in four years.[7] These rates demonstrate the need for continued reflective practice and possible programmatic change at the curriculum level.[8]

In 2011 Montgomery College English faculty felt mounting pressure to meet the College’s completion goals, maintain high academic standards, and provide the support so many students need to persist in college. Therefore the English (now English and Reading) Department underwent a course sequence review. Out of this curricular review, the Program for the Advancement to College English (formerly ACE) emerged.

high academic standards, and provide the support so many students need to persist in college. Therefore the English (now English and Reading) Department underwent a course sequence review. Out of this curricular review, the Program for the Advancement to College English (formerly ACE) emerged.

How do student data inform the development of the program?

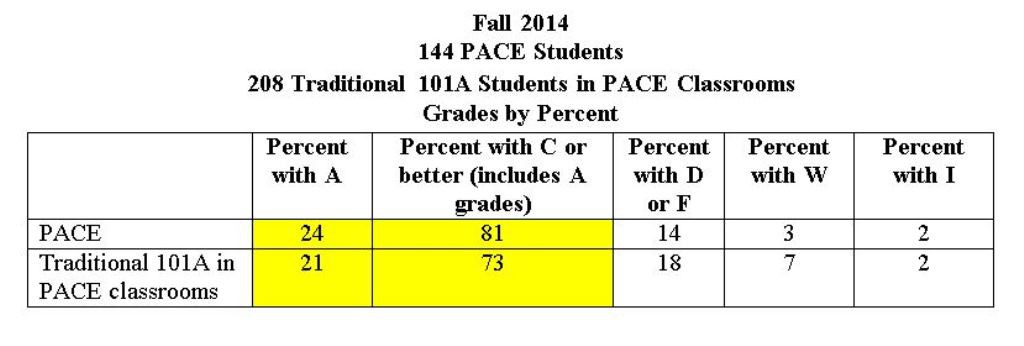

Currently the PACE program is growing each year and moving the needle toward higher student success rates both in the ENGL 101A class and the second composition course, ENGL 102/103. At the time of this writing, PACE sections for fall 2015 are largely full with the potential for additional PACE 101A classes in the fall schedule. The first chart demonstrates fall 2014 ENGL 101A PACE data class grade results (n = 352).[9]

Figure 1. The chart shows the percentages of grades in the 101A PACE classes. During fall 2014, the PACE students achieved higher grades on average than the non-PACE students in the same class. These 144 PACE students did not take any developmental English or reading classes. With faculty support and dedication to their course work, 81 percent of these PACE students earned a grade of C or higher in first-semester composition.

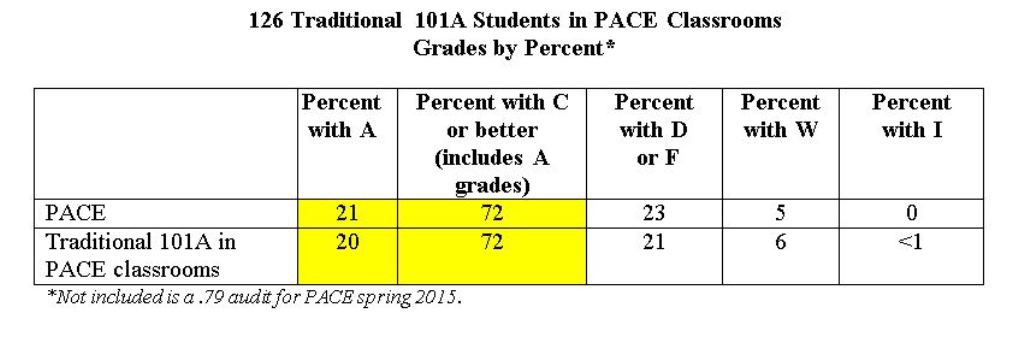

In spring 2015, we found that grade percentages dropped slightly as did the number of students enrolling in the program. However, higher rates of achievement for PACE than for non-PACE students remain the trend. The second figure demonstrates the spring 2015 class grade results (n=187).[10]

Figure 2. The chart shows the percentages of grades in the 101A PACE classes. During spring 2015, the PACE students on average achieved grades higher or equal to non-PACE students in the same class. These 61 PACE students did not take any developmental English or reading classes. With faculty support and dedication to their coursework, 72 percent of these PACE students earned a C or higher in first-semester composition.

Figure 2. The chart shows the percentages of grades in the 101A PACE classes. During spring 2015, the PACE students on average achieved grades higher or equal to non-PACE students in the same class. These 61 PACE students did not take any developmental English or reading classes. With faculty support and dedication to their coursework, 72 percent of these PACE students earned a C or higher in first-semester composition.

The data on student success in ENGL 101A PACE prompted further review of PACE student success in ENGL 102/3. Our available data at this time shows that of the PACE students from fall 2013 who were successful in ENGL 101A (n = 96), 83 percent attempted ENGL 102/3. Of those students who attempted the course, 86 percent were successful.[11] Overall, 52 percent of the PACE students from fall 2013 have passed ENGL 102/3, higher than the state average.[12] In a longitudinal review of fall 2012 data (n=85 at the Rockville Campus), we found that 69 percent of the successful PACE students have attempted ENGL 102/3. Of those students, 83 percent were  successful. Three semesters after 2012, 65 percent of the students in PACE were still attending Montgomery College. This information cuts both ways: high numbers are still enrolled, but potentially high numbers have not completed a degree. Further data review is warranted. Overall, the data tell us we have work to do, but we have discovered some meaningful information to help guide student success and curricular and programmatic decision-making – a writing sample for review and placement, faculty collaboration in the form of tutoring in the classroom, and student success strategies.[13]

successful. Three semesters after 2012, 65 percent of the students in PACE were still attending Montgomery College. This information cuts both ways: high numbers are still enrolled, but potentially high numbers have not completed a degree. Further data review is warranted. Overall, the data tell us we have work to do, but we have discovered some meaningful information to help guide student success and curricular and programmatic decision-making – a writing sample for review and placement, faculty collaboration in the form of tutoring in the classroom, and student success strategies.[13]

How does faculty input inform the development of the program?

In the fall of 2014, a program evaluation reviewed one part of the PACE program: the tutoring component. Through semi-structured interviews and classroom observations, a semester-long qualitative study of in-class tutoring in PACE classrooms was conducted to see how the program is developing in terms of its original intent.[14] The following question guided the review of the tutoring component: According to PACE faculty teachers and tutors, how is thetutoring component of the PACE program supporting the success of PACE students in the English 101A class? In this section, we share three of the findings.[15]

Finding #1: Tutors provide academic support that benefits all students.

Tutoring supports critical thinking in essay drafting. Interviewee #1 shared quotes from her students about the academic support they feel in the class: “The benefit of the tutor is ever-present. I can ask multiple questions and bounce ideas off my professor and tutor.” Interviewee #2 noted that tutors can “pinpoint specific writing or grammatical issues or writing tactics.” He also noted that he taught a PACE class that was not issued a tutor because of a scheduling mishap. He explained, “I got to experience both sides: there is a big difference in terms of working with students closely on their writing” when a tutor is not present.

Finding #2: PACE supports the motivational needs of students such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, and persistence.

Tutors can tap into student interests and capabilities. Interviewee #2 has served as both tutor and teacher. In one instance, the students appeared to prefer his help over the lead teacher’s. In another instance, when he served as the lead teacher, some of the students tended to gravitate toward the tutor. The tutor was able to tap into a student’s thought process and help the student produce good work. Interviewee #2 also noted the value of PACE as a way to retain the students. He feared students would drop out without the “interaction, the connection to the teaching staff.”

Finding #3: Collaboration is the cornerstone of the PACE program, providing interaction between three key individuals: tutor, teacher, and student.

In the ENGL 101A PACE classroom, collaboration is vital. Teachers and tutors shared ways they were positively impacted by the PACE program. In an observation, the tutor assisted a student with paragraph construction. She signaled for the lead teacher to assist as well, bringing teacher, student, and tutor into conversation together. This type of modeling of academic discourse supports the students, teachers, and tutors in teaching and learning the writing process in the composition classroom.

What is the future of PACE?

The Montgomery College PACE program is finding new ways to support pre-college-ready students in the form of academic and motivational supports, bolstering their journey from access to success.[16] In this important era of student success as the “primary goal of Montgomery College,” PACE is setting a good pace for our students.[17] Based on data collection, this growing program’s service to Montgomery College is multifaceted. It accelerates student completion and brings faculty into collaboration and communication about student needs. As we continue to implement and grow this program, we hope that more students will benefit from the in-class tutoring and connectedness they feel to their academic experience at Montgomery College. As faculty, we will continue to be motivated by the growth of this program, the progress of our students, and the dedication of our peers.

Footnotes

- Rebecca Eggenschwiler and Samantha Streamer Veneruso, “PACE Data Collection,” (Unpublished program evaluation, Montgomery College, 2015): 1.

- Montgomery College Office of Institutional Research and Analysis, “Grades in Fall 2014 for Selected ‘Gateway’ Courses” (Montgomery College, 2015), 1.

- Eggenschwiler and Streamer Veneruso, “PACE Data Collection,” 1.

- Andy Hargreaves and Michael Fullan, Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School (New York: Teachers College Press, 2012), 41.

- Peter Adams, Sarah Gearhart, Robert Miller, and Anne Roberts. “The Accelerated Learning Program: Throwing Open the Gates,” Journal of Basic Writing (CUNY) 28, no. 2 (2009): 50.

- Craig Clagett, “The Maryland Model of Community College Student Degree Programs,” Planning for Higher Education Journal 41 (2013): 9.

- Clagett, “The Maryland Model,” 9.

- Donald Schon, The Reflective Practioner: How Practitioners Think in Action, Vol. 5126 (New York: Basic Books, 1983), 49.

- Eggenschwiler and Streamer Veneruso, “PACE Data Collection,” 1.

- Eggenschwiler and Streamer Veneruso, “PACE Data Collection,” 1.

- Eggenschwiler and Streamer Veneruso, “PACE Data Collection,” 1.

- Clagett, “The Maryland Model,” 9.

- Michael Fullan, The New Meaning of Educational Change (New York: Teachers College Press, 2007), 29.

- Carol Weiss, Methods for Studying Programs and Policies (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998), 75.

- Elizabeth Benton, “Program Evaluation: In-Class Tutoring in the Program for the Advancement to College English.” (Unpublished coursework, The George Washington University, 2014): 11-15.

- American Association of Community Colleges. “Reclaiming the American Dream: Community Colleges and the Nation’s Future,” (Report from the 21st-Century Commission on the Future of Community Colleges, Washington, DC, 2012): ix.

- Montgomery College Board of Trustees, 41000, 1.

References

Adams, Peter, Sarah Gearhart, Robert Miller, and Anne Roberts. “The Accelerated Learning Program: Throwing Open the Gates.” Journal of Basic Writing (CUNY) 28, no. 2 (2009): 50-69.

American Association of Community Colleges. “Reclaiming the American Dream: Community Colleges and the Nation’s Future.” Report from the 21st-Century Commission on the Future of Community Colleges, Washington, DC, April 2012.

Benton, Elizabeth. “Program Evaluation: In-Class Tutoring in the Program for the Advancement to College English.” Unpublished coursework, The George Washington University, 2014.

Clagett, Craig A. “The Maryland Model of Community College Student Degree Programs.” Planning for Higher Education Journal 41 (2013): 49-68. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-381056272/the-maryland-model-of-community-college-student-degree.

Eggenschwiler, Rebecca and Samantha Streamer Veneruso. “PACE Data Collection.” Unpublished program evaluation, Montgomery College, 2015.

Fullan, Michael. The New Meaning of Educational Change. New York: Teachers College Press, 2007.

Hargreaves, Andy, and Michael Fullan. Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. New York: Teachers College Press, 2012.

Montgomery College Office of Institutional Research and Analysis. “Grades in Fall 2014 for Selected ‘Gateway’ Courses,” Montgomery College, 2015.

Montgomery College Board of Trustees, 41000.

Schön, Donald A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Vol. 5126. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Weiss, Carol H. Methods for Studying Programs and Policies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998