By Professor Tiffany Banks On Tuesday, September 30th , students from my COMM 108: Foundations…

By Professor Rebin Muhammad

On August 5, our Honors 256 HB: Islamic Geometric Patterns class visited the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) to explore an exhibition titled “Pattern and Paradox: The Quilts of Amish Women.” Initially, our syllabus (developed by myself and Professor David Carter from the art department) planned for a visit to the National Gallery of Art to view the works of Crockett Johnson, known for his geometric paintings rooted in the mathematical histories of Archimedes, Newton, and Euler, such as the one below titled Proof of the Pythagorean Theorem (Euclid).

However, on one of my museum visits to SAAM via SFF in Spring 2024, we saw the beautiful Amish Quilt exhibition. After the visit I started speaking with Professor David Carter, the co-teacher of the class, and agreed that this would be an perfect addition to our course to complement our trip to the Diyanet Center where students explored Islamic Geometric Patterns hands-on.

By Week 8 of the course, students had developed a solid understanding of Islamic Geometric Patterns (IGP), through creating them, analyzing them, and learning to distinguish between patterns from different cultures. This trip aimed to expose students to a completely different yet strikingly parallel form of geometric art. The Amish quilts, with their bold and intricate designs, provided a perfect opportunity to explore connections and contrasts between two vastly different traditions of geometric creativity.

We met at the museum’s entrance around 10 a.m., ready to explore. One student even brought their sibling, and many of us took the metro individually or as a team. The choice to visit the Quilts of Amish Women exhibition stemmed from its striking parallels to IGP. Many of these quilts incorporate geometric elements that naturally invite comparisons. Students were astounded to see how patterns from such different cultural contexts—separated by thousands of miles—could appear so similar.

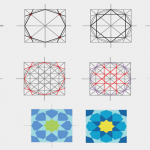

Before the visit, we provided students with a one-page guide outlining goals while leaving room for their creativity and curiosity to shine. The idea was to encourage students to interpret the patterns and find some personal connections themselves, similar to how Islamic artisans historically created intricate designs using only basic tools like a compass and straightedge. Below is one of those examples.

Inside the museum, students immersed themselves in the exhibition, documenting observations through photos and notes. The assignment was deliberately unstructured, allowing for personal exploration and freedom in interpreting the artworks. Some students paired up to discuss a quilt, while others studied the intricate details of the patterns on their own.

Inside the museum, students immersed themselves in the exhibition, documenting observations through photos and notes. The assignment was deliberately unstructured, allowing for personal exploration and freedom in interpreting the artworks. Some students paired up to discuss a quilt, while others studied the intricate details of the patterns on their own.

This free-form approach sparked meaningful conversations. Rimsha, for instance, shared how certain patterns reminded them of art they’d seen in their own culture but never considered as “art” due to the hardships faced in their region. This led to a discussion on how art appreciation can diminish in war-torn regions where survival takes more importance than beauty—a perspective I could personally relate to, having grown up in Iraq during the 1980s and witnessing multiple wars. It wasn’t until I came to the U.S. that I began to fully appreciate Islamic geometric art.

Another student, Lucinda, connected to the exhibit on a deeply personal level. For her, the quilts evoked memories of her grandmother, an accomplished quilter whose designs mirrored some of the patterns in the exhibit. This connection was so strong that, after the visit, Lucinda brought some of her grandmother’s quilts to class, further enriching our discussions. In a way, her grandmother became part of the class experience, contributing to our exploration of the shared language of patterns. As Lucinda wrote in her assignment: “Growing up surrounded by quilts due to a grandmother who is an avid quilter, I was excited to see how the patterns used in the exhibit would overlap with my grandmother’s, and what quilts looked like a hundred years ago.”

Many Amish quilts share common design elements such as central diamonds, rectangular bars, or grids of repeated shapes intersecting in various ways. One quilt, however, stood out for its interlocking circles—a pattern that prompted a lively discussion. Its resemblance to Islamic geometric designs led us to speculate whether the artist might have been inspired by such patterns, perhaps seen during a museum visit

This discussion naturally extended to how artists draw inspiration. For instance, we explored the work of M.C. Escher, the Dutch artist who studied Islamic geometric art during a visit to Spain’s Alhambra. (Also Professor David led an activity similar to Escher’s style in class) Though his later works evolved into something uniquely his own, their roots in IGP are unmistakable. We also traced this exchange of artistic influences back further in history, noting how Muslim artisans adapted and expanded upon Greco-Roman patterns to develop their own complex designs.

Rimsha also reflected on the connections between the two art forms, saying, “The Amish and Islamic designs both emphasize harmony and balance. The visit made me realize the importance of preserving traditional art forms for future generations.” Lucinda, meanwhile, noticed a key difference between Islamic Geometric Patterns and Amish quilts. She stated, “One thing that stood out to me right away was how the colors differed between Amish and Islamic patterns. The Amish artworks quite often used warm colors, like pink or red, accentuated by a black base, whereas Islamic patterns, such as the ones we saw at the Diyanet Center, seem to tend toward blue or gold on white.”

This trip was a bridge between two worlds, an opportunity to deepen students’ appreciation of art and mathematics through a cross-cultural comparison. By connecting Amish quilts to Islamic Geometric Patterns, students saw how geometry transcends cultural and geographical boundaries. This realization sparked deeper conversations about art, heritage, and the universal human drive to create beauty—even amidst adversity.

This visit enriched our course in unexpected ways, creating lasting impressions and new avenues of exploration. For Lucinda, it deepened her appreciation of her grandmother’s work. For others, it was an invitation to rediscover and reframe the beauty they may have overlooked in their own cultural traditions. For all of us, it was a reminder of the universal language of patterns—a language that speaks across time, space, and cultures. Joshua stated, ““By witnessing the artistry of the Amish women my appreciation for quilting was completely elevated. The standards I associated with quilting in general were totally changed. The act of quilting had never registered as an actual piece of art before this class excursion.”

References:-

This Post Has 0 Comments