By Professor Tiffany Banks On Tuesday, September 30th , students from my COMM 108: Foundations…

by Professor Matthew Decker

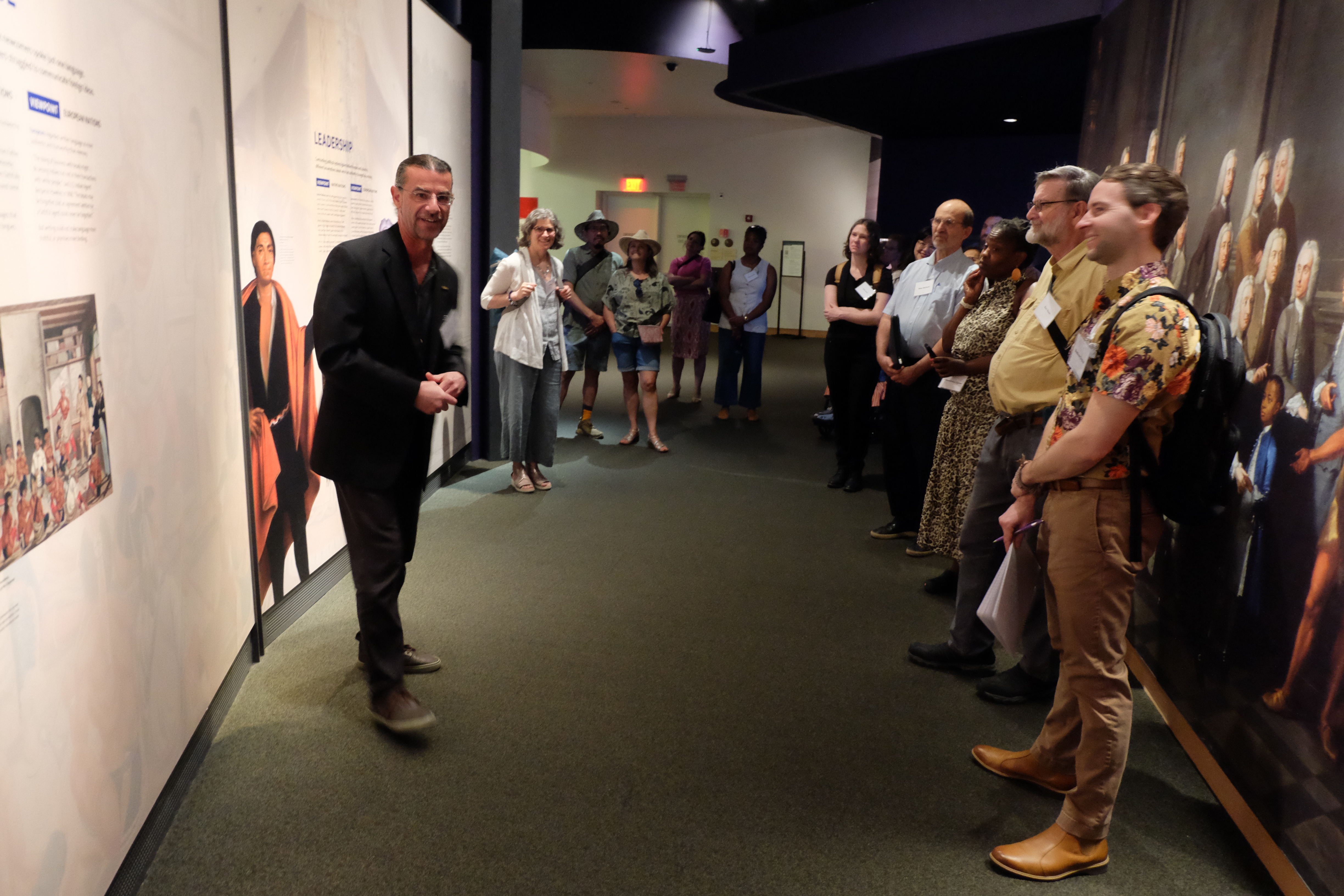

The Fellows were in especially esteemed company as Maria Marable-Bunch, Associate Director of Museum Learning and Programs, welcomed them to the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) last Thursday. While she shared appropriately glowing reviews of the NMAI curators and educators who would be our guides through two exhibits, Nation to Nation and Americans, she was quick to underscore a distinguishing element of NMAI’s robust online educational resources: “classroom teachers work on the materials we create.” What sweet music to our ears! Perhaps this is just one reason why Native Knowledge 360° is truly one of the most impactful and well-cared for spaces for museum-informed teaching materials. Public projects, interpretation, research and scholarship, and close ties to the Native communities define the NMAI mission, and—no matter the entry point—there is rich history to explore and share.

Renee Gokey, the Teacher Services Coordinator at NMAI and a citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, invited us to explore the online opportunities first. She explained that Native Knowledge 360° is designed to transform teaching about Native peoples in K-12 classrooms. The ten themes that define NK360°, though, are easily scalable. There’s also no denying the impressive scope in terms of content and discipline. Want to view a prerecorded professional development webinar? Interested in testing a Mayan math game? How about telling a better story of the “First Thanksgiving”? These represent only a drop in the bucket of what NK360° can offer you and your students. For the subject selection of Environmental Science alone, you will discover 17(!) readymade resources, including a website, teaching posters, digital lessons, and more.

For those interested in a physical museum visit, too, you will discover the rich synergy that infuses NMAI’s educational offerings, many of which are directly informed and inspired by the museum’s permanent and temporary exhibits. Thanks to Curator Christopher Lindsay Turner, the Cultural Research Specialist at NMAI, we were treated to a tour of Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations. This sprawling showcase of Native history—united by an overhead wampum motif—unfolds the shared history of approximately 600 Native tribes, a history best explored through the lens of a primary document: the treaty. Designed in response to a collection of the museum’s inaugural but since retired exhibits, including Our Peoples: Giving Voice to Our Histories and Our Universes: Traditional Knowledge Shapes Our World, Nation to Nation serves to highlight documents that are not only especially significant to Native peoples but also evergreen. As Lindsay Turner enthusiastically shared, “There is always a new story to tell.” Ultimately, Nation to Nation is a dynamic space filled with intercultural exchanges ripe with story, artifacts, and even symbolism.

Given the sheer size of the exhibit and the wealth of information on display, it’s easy to become a bit overwhelmed as one navigates the space, so I highly recommend this video overview, which includes discussion of one of the earliest treaties: the two-row wampum belt, or Guswenta. Shared between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch settlers, the belt is inlaid with purple rows of beading intended to symbolize two parallel paths. They agreed to a harmonious existence, an enduring peace as these unique nations traveled the waters side by side. Of course, the written treaties on display in Nation to Nation highlight how easily the spirit of the Guswenta could be lost to power-mongering, dispossession, and terrible violence. An NK360° case study captures the devastating lifecycle of a treaty held between the United States and the Potawatomi Nation, which concluded with the Potawatomi Nation’s forced removal to Indian Territory, an event that left 42 dead on their two-month long journey from Indiana to reservation lands in Kansas.

Given the sheer size of the exhibit and the wealth of information on display, it’s easy to become a bit overwhelmed as one navigates the space, so I highly recommend this video overview, which includes discussion of one of the earliest treaties: the two-row wampum belt, or Guswenta. Shared between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch settlers, the belt is inlaid with purple rows of beading intended to symbolize two parallel paths. They agreed to a harmonious existence, an enduring peace as these unique nations traveled the waters side by side. Of course, the written treaties on display in Nation to Nation highlight how easily the spirit of the Guswenta could be lost to power-mongering, dispossession, and terrible violence. An NK360° case study captures the devastating lifecycle of a treaty held between the United States and the Potawatomi Nation, which concluded with the Potawatomi Nation’s forced removal to Indian Territory, an event that left 42 dead on their two-month long journey from Indiana to reservation lands in Kansas.

This, unfortunately, is not an unfamiliar story for Native tribes. Today, in fact, Native Americans represent only 1% of the U.S. population, a startling statistic that drove an important question posed by Renee Gokey when she escorted us to the Americans exhibit: Why are there images of Native peoples everywhere? It’s a fascinating point made all the more palpable by the artifacts in Americans’ open gallery. Here are just a few examples: a Native American Barbie doll, 1996, a Saturday Evening Post magazine cover, and the Land O’Lakes Butter carton.

To delve deeper, Gokey invited us into a dialogue informed by The International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. Together and independently, we explored the images and objects on display as we considered questions, like “Who taught you about Native Americans?” “What are the false, incomplete, or more complete narratives?” and “Do you have any examples of your story as told by others?” These questions guided us as we engaged images that toe the line between nostalgia, surprise, and even disgust, ultimately leading us to discovery. The Great Sioux War of 1876, which included the legendary Battle of the Little Bighorn, coincided with technological advancements that forged the literal stereotype in printing. The reproduced stories and images of this battle solidified representations of the victorious Native warrior, the bloodthirsty “savage,” and other stereotypes that live on today, most notably in advertising.

considered questions, like “Who taught you about Native Americans?” “What are the false, incomplete, or more complete narratives?” and “Do you have any examples of your story as told by others?” These questions guided us as we engaged images that toe the line between nostalgia, surprise, and even disgust, ultimately leading us to discovery. The Great Sioux War of 1876, which included the legendary Battle of the Little Bighorn, coincided with technological advancements that forged the literal stereotype in printing. The reproduced stories and images of this battle solidified representations of the victorious Native warrior, the bloodthirsty “savage,” and other stereotypes that live on today, most notably in advertising.

As we concluded our visit, Gokey invited us to explore one final gallery—this one dedicated to the Trail of Tears. Given the heavy content we had just absorbed, ending in this gallery could have been easily dispiriting. How can a museum visitor unpack the 20-year ethnic cleansing of Native Americans? A Fellow and I gravitated toward a picture of a woman we originally misinterpreted to be in favor of Native displacement, but, as we read further, we were introduced to Hetty Elizabeth Beatty, a vocal representative of the ladies in Steubenville, OH, who petitioned against Indian removal. Their story is a fascinating snippet of countless untold stories of resistance that will inspire visitors, especially as they witness contemporary injustices.

Gokey ultimately asked, “Does this exhibition change how you would tell the story of America?” And, I know it has for me. As a pessimist, I tend to focus on the darker pockets of history, recognizing how easily it repeats. But stories as simple and nuanced as a lone petition from a group of early activists give me hope. Rather than read headlines and watch the news and shake heads in defeat, we can find our people, we can contribute to meaningful action, we can find purpose as the David standing in the way of the Goliath.

photos by Matthew Decker and Denise Dewhurst

This Post Has 0 Comments