By Professor Tiffany Banks On Tuesday, September 30th , students from my COMM 108: Foundations…

by Professor Ron Nunn

By Ronald Nunn, Anthropology

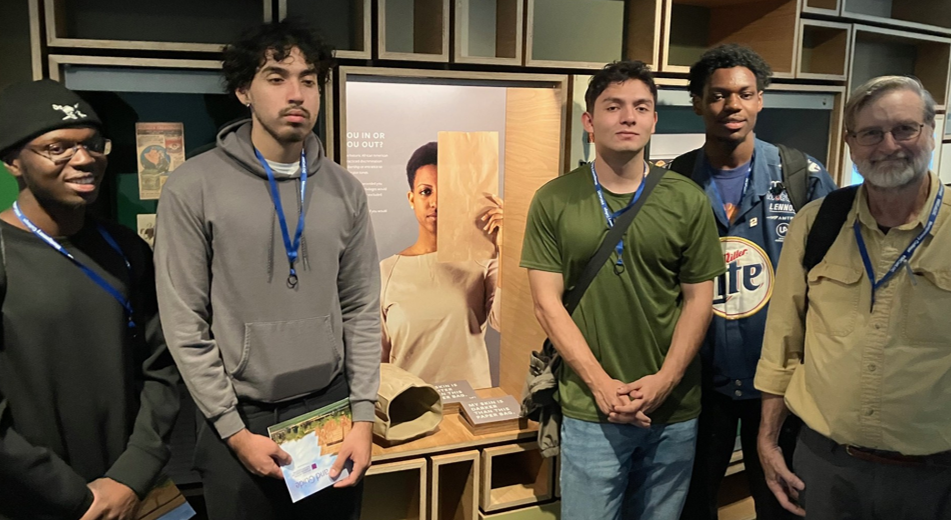

On Friday Oct. 3rd, 2025, a visit was made to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) with the MC Anthropology 215 Class, Human Evolution and Archaeology. We rode the metro together after having walked from our classroom on the Takoma Park/Silver Spring Campus about 20 minutes, to the Takoma Park Metro Station. It was a beautiful, sunny fall day as we arrived on the National Mall and again walked from the Smithsonian Metro Stop over to the Museum.

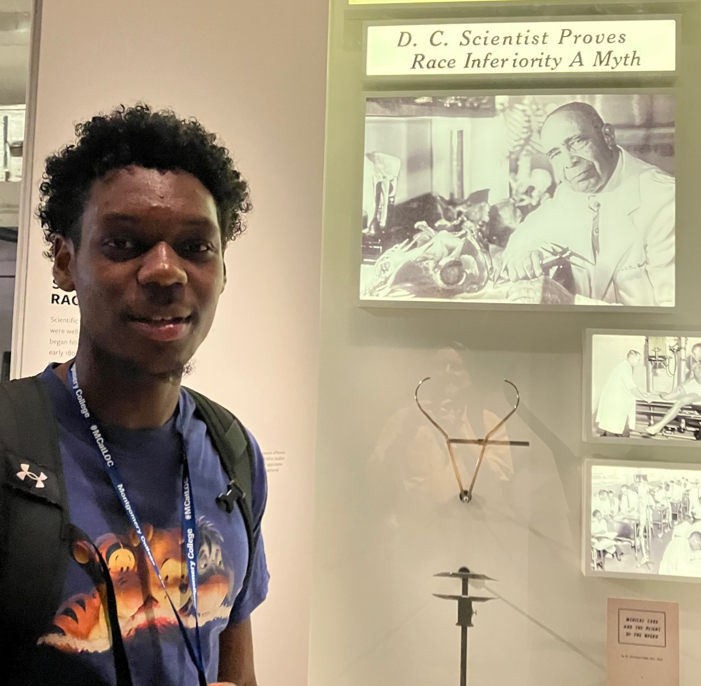

We had five students plus one friend and my wife, Kay Marten, who volunteers at the museum several days each month and who acted as our guide. Kay explained the purpose of the three basement floor levels before we proceeded up to the third floor (L3) and entered the gallery called “Making a Way out of No Way”. There, she explained that some of the exhibits were there because for many years African Americans were excluded from many educational and even religious institutions. I asked my students to look at the exhibit dedicated to Dr. William Montague Cobb, a Medical Doctor and the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in Physical Anthropology until after the Korean War.

Because our course, (ANTH 215) is an introduction to Physical and Biological Anthropology, the same discipline of Anthropology that Dr. Cobb studied, I wanted students to understand the significance of his career as a Medical Doctor and professor of Anthropology at a time when Racial classification was very much in vogue and races were not considered to have equal standing between them. It is important to mention that Dr. Cobb worked briefly at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History following his medical and anthropological training and was exposed, first hand, to the work or another famous Physical Anthropologist Dr. Ales Hrdlicka. Dr. Hrdlicka was well known for his collection of human skeletal material and for his attempts, in an era of eugenics, to prove that racial hierarchy existed. Today, this is known as “Scientific Racism” or the attempt to prove scientifically, that there were measurable differences and racial markers that could distinguish races from each other. Just as other physical anthropologist in his day were doing, Dr. Cobb collected skeletons and crania but with a quite different purpose in mind. Dr. Cobb spent most of his career teaching human anatomy and osteology at the Howard University Medical School where he conducted scientific measurements of his own resulting in numerous publications disputing racial hierarchy and proving that racial inferiority was a myth. One widely publicized example in the exhibit showed a photograph of Dr. Cobb measuring the famous track star Jesse Owens who was the fastest sprinter in the 100-meter race in the 1936 Olympics. Owens is shown in Cobb’s lab following a publication proving that he was no super athlete or that he held any unusual athletic qualities that were the result of him being of African American extraction as was widely assumed at the time.

While viewing the exhibit, one student asked how the “N” word become a racial slur? I responded by saying that the “N” word was a pejorative form of the word Negro which in Spanish is “Negra” which simply means “black”. Another student who speaks both Spanish and French confirmed that was the correct meaning of the word. I indicated that there were many aspects of racism in America and Dr. Cobb used science in order to counter the long-held belief that African Americans had smaller brains and were, therefore, less intelligent. Pictured with Dr. Cobb were several of his “calipers” which are instruments used by physical anthropologists to measure human bones and especially skulls.

While viewing the exhibit, one student asked how the “N” word become a racial slur? I responded by saying that the “N” word was a pejorative form of the word Negro which in Spanish is “Negra” which simply means “black”. Another student who speaks both Spanish and French confirmed that was the correct meaning of the word. I indicated that there were many aspects of racism in America and Dr. Cobb used science in order to counter the long-held belief that African Americans had smaller brains and were, therefore, less intelligent. Pictured with Dr. Cobb were several of his “calipers” which are instruments used by physical anthropologists to measure human bones and especially skulls.

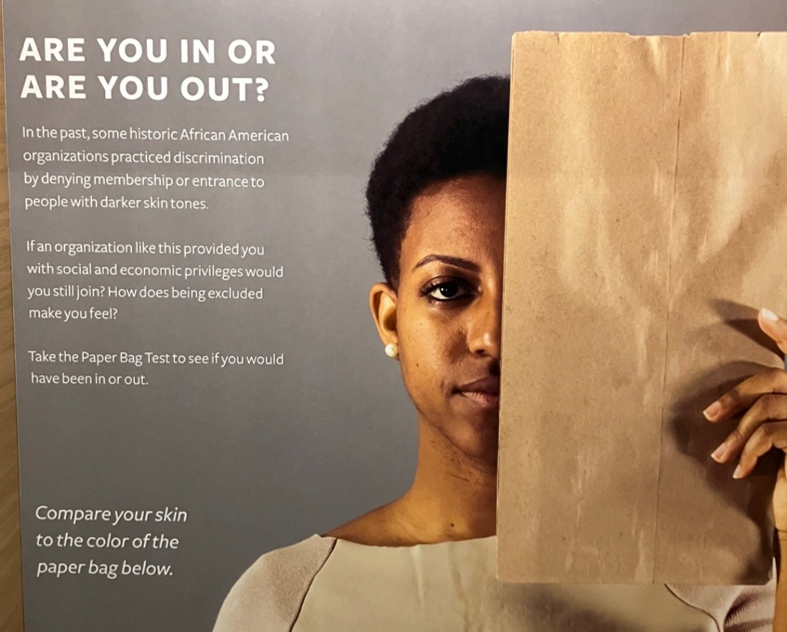

Once finished with the Cobb exhibit we moved to the Culture Galleries on the 4th floor (L4), where we viewed the exhibit called “Are you in or are you out” illustrating what was called “The paper bag rule”. The paper bag rule was that if your skin color was lighter than that of a paper bag you could gain membership in some organizations. This afforded some African Americans opportunities beyond those that their darker friends and family members were able to obtain.

After viewing the exhibit, one student said that he had some cousins that were very light in skin completion and that all his other family members had darker skin tones. He then made a connection to our discussion in class regarding Mendelian or “simple” inheritance involving only one gene with alternate forms called alleles. In class I gave an example of a black rabbit mating with a white rabbit and instead of the offspring resulting in a grey rabbit as Charles Darwin would have understood inheritance, the results were all black rabbits. Then in the second generation the offspring were usually three black and one white rabbit illustrating that the recessive allele for white could re-appear fully un-blended somewhere else down the line of inheritance.

The student wanted to know if the example applied to his family members. I had to explain that actually the rabbit example did not apply to human skin color because skin color is “polygenic” meaning skin tones are governed by more than one gene resulting in a more continuous distribution of genetic traits like skin tones. Therefore, the union of a black human with a white human would be more likely to result in a “blended” result or a brown human which is how Darwin understood inheritance before the discovery of genetics. This was a bit of a head scratcher for the student because he had missed the discussion on polygenic inheritance held on a different day in class.

Another student then brought up the fact that the reason that some people had lighter skin tones in the African American population was due to the impregnation of slaves by their white owners during the period before the Civil War. Another student disagreed with this based on the fact that skin tones also vary with latitude with darker skin tones in areas with higher UV radiation. This example was discussed in class as well. I indicated that both examples are true but that skin tone variation discussed in the exhibit was probably due to admixture and racial mixing in the first case and mutations due to UV radiation according to latitude adaptation in the second case.

Lighter or darker skin tones do vary according to long term adaptation to UV radiation. The cultural response to skin tones, however, was the overall point and the reason why I had selected the exhibit for students to see. The resulting discussions between the students on the biological reasons for various of skin tones was an aspect I had not considered but highly engaging and interesting on many levels none the less.

I considered the visit to the two exhibits at the NMAAHC very much a win as judged by the un-anticipated questions that were asked which resulted in a clear case of collaborative thinking about the exhibit and relating that back to material presented in the classroom regarding both the biological and the social aspects of race in America. The reasoning behind the selection of the first exhibit was intended to focus on Anthropologists who had used science both to justify and dispel aspects of race arriving at vastly different conclusions thus illustrating the futility of racial classification schemes for humans in general.

My students, however, seemed to accept the notion that anthropologists had been involved in the scientific quest both to prove and to disprove race as a given. They seemed to understand this idea so well that there were no penetrating questions or even comments regarding that topic and instead the questions were aimed at more fundamental aspects of how the language surrounding race came into existence.

In the second exhibit regarding skin color the reasoning for selecting the exhibit were aimed at the social consequences of phenotype or outward appearance and community acceptance. Again, instead of focusing as, I had intended, on the social aspects of skin color and race, the questions from students incorporated material presented in class that they then applied to the practical presentation of varying skin tones and the underlying biological causes. Overall, the museum visit for me was very much a case of the Professor learning from his students just as much, if not more, than the students learning from being exposed to new experiences at the Smithsonian. These are the positive aspects of the Oct. 4th, 2025 visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Following are some anticipated but as yet, unrealized, down sides.

In the second exhibit regarding skin color the reasoning for selecting the exhibit were aimed at the social consequences of phenotype or outward appearance and community acceptance. Again, instead of focusing as, I had intended, on the social aspects of skin color and race, the questions from students incorporated material presented in class that they then applied to the practical presentation of varying skin tones and the underlying biological causes. Overall, the museum visit for me was very much a case of the Professor learning from his students just as much, if not more, than the students learning from being exposed to new experiences at the Smithsonian. These are the positive aspects of the Oct. 4th, 2025 visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Following are some anticipated but as yet, unrealized, down sides.

The SFF assignment for the students this semester in ANTH 215 is to produce a digital story on the topic: “What race means to me”. It is not asking students to define race but rather to interpret the meaning and its impact in their own lives and from their own point of view. From the classroom discussions held so far and given the fact that the majority of the students are of African extraction or African American; It is anticipated that the digital story responses to this question will be highly personal and may have little or no reference at all to any materials or topics engaged with on the field trip. It is also an open question, given the topic, that there will be any utilization of materials available in the learning labs, virtual tours or photographic databases held by the Smithsonian. In addition, only five out of fifteen students made the field trip which was partly due to the fact that the field trip was hastily rescheduled following the anticipated closing of the Smithsonian Museums due to the government shut down that began on Oct. 1st, 2025. The unfortunate rescheduling eliminated a portion of the class that could not reschedule on short notice because of work or prior commitments. Such is life in our complex world in these challenging. and yet interesting, times. Ultimately, I have faith in my highly adaptable and creative students who come from so many different backgrounds, that they will produce interesting and highly engaging digital stories in any case.

This Post Has 0 Comments