Striving for inclusive excellence, Montgomery College is committed to fostering an inclusive community of students, faculty, and staff. The College is continuously working on helping employees develop skills that serve the community.

Striving for inclusive excellence, Montgomery College is committed to fostering an inclusive community of students, faculty, and staff. The College is continuously working on helping employees develop skills that serve the community.

The Office of E-Learning, Innovation, and Teaching Excellence (ELITE) and the Office of Equity and Inclusion (OEI) are proud to sponsor this Inclusion and Diversity Calendar for MC students and employees. This calendar is intended to provide an awareness of various observances across our college community. The calendar does not reflect the multiple opportunities and events sponsored by ELITE or OEI. Please visit the OEI website, and MC Learns through Workday to learn more about the college’s Equity and Inclusion professional development opportunities and special events.

Calendar Content: Workplace Diversity and Inclusivity D&I Calendar

What is UDL?

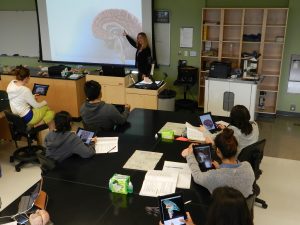

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an educational framework that provides a flexible approach to teaching and learning, aiming to accommodate the diverse learning needs and preferences of all students. UDL emphasizes proactive design and the creation of inclusive learning environments that remove barriers to learning and maximize educational opportunities for everyone, including students with disabilities or varying learning styles.

In this video series, Professor Andrews-Williams discusses Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and the set of principles that supports the learning needs of all students.

Part 1

This video defines and explains the construct of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). The UDL framework is guided by three principles supported by neuroscience to provide multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement.

Part 2

The primary objective of this video is to delve into the fundamental principle of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) known as Representation.

Part 3

The central aim of this video is to thoroughly explore the fundamental principle of Engagement, which is an integral component of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and focuses on the motivation and purpose behind the process of learning.

Part 4

The primary focus of this video is to thoroughly explore the fundamental principle of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) known as Action and Expression, which encompasses the diverse ways in which learners can effectively demonstrate their understanding and knowledge.

Five Approaches to a Multicultural Education

What is multicultural education?

As early as 1987, educators like Christine Sleeter and Carl Grant (1987) described and categorized education initiatives in and for the culturally diverse US society. They studied educational practices that focus on the culturally diverse students in US classrooms and/or on the preparation of students to function in the culturally diverse US society. They proposed the presence of five approaches, all of which can be included under the umbrella term multicultural education.

Achieving Desired Equity and Inclusion

Data and DEI: Practical Insights to Achieving Desired Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Changes

Of concern to HR and organizational leaders is evidence that shows DEI initiatives and goals failing despite senior-level desire and investments to achieve progress in diversity, equity, and inclusion. One area of relevance to MC is the challenge of meeting desired diversity targets in recruitment.

Strategies for Reducing Implicit Bias in the Classroom

What Is Implicit Bias and How Does It Impact a Learning Environment?

According to the National Institutes of Health (2022), “Implicit bias is a form of bias that occurs automatically and unintentionally, that nevertheless affects judgments, decisions, and behaviors” (para. 2).

The Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.) provides a similar definition: “Implicit bias refers to unconscious attitudes, reactions, stereotypes, and categories that affect behavior and understanding” (para. 1).

As mentioned in these definitions, implicit bias often occurs unconsciously but offends people exposed to it. Many factors are associated with such behavior. They may include socialization from childhood, media exposure, and cultural environment. In a learning environment or classroom, implicit bias can affect a teacher’s perceptions of students and judgment of their performance. If left unchecked, implicit bias in the classroom may contribute to inequities and discrimination, unfair grading, and poor academic relationships between the teacher and the student. Many factors are associated with such behavior, including childhood socialization, media exposure, and cultural environment. In a learning environment or classroom, implicit bias can affect a teacher’s perceptions of students and judgment of their performance. If left unchecked, implicit bias in the classroom may contribute to inequities and discrimination, unfair grading, and poor academic relationships between the teacher and the student.

Democratizing Classroom Participation: Narrowing the Opportunity Gap.

The video proposes strategies to become aware of lower transfer and graduation rates, as well as higher DFW rates, for minoritized students. Strategies are offered to innovate teaching practices for diversity, equity, and inclusion.

What are microaggressions?

What are microaggressions?

Dr. Chester M. Pierce of Harvard University first coined the term “microaggression” in 1970 to denote common insults and dismissals experienced by African Americans. The term was later generalized to include other marginalized groups such as women and people with disabilities.

Dr. Derald Wang Sue of Columbia University defines microaggressions as “brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain individuals because of their group membership.”

In the classroom, these microaggressions follow a continuum from nonverbal gestures and forgetting to acknowledge someone to more active behaviors such as directly minimizing someone’s experience or using inappropriate language.

Types of Microaggressions

1. Failing to learn to pronounce or continuing to mispronounce the names of students after they have corrected you.

2. Scheduling tests and project due dates on religious and cultural holidays.

3. Calling on, engaging, and validating one gender, class, or race of students while ignoring other students during class.

4. Denying the experiences of students by questioning the credibility and validity of their stories.

5. Assuming the gender of any student.

6. Continuing to misuse pronouns even after a student of any gender shares the pronouns they use with you.

7. Assigning projects that ignore differences in socioeconomic class status and inadvertently penalizing students with fewer financial resources.

8. Assuming all students have access to and are proficient in the use of computers and applications for communications about school activities and academic work.

9. Assuming that students of particular ethnicities must speak another language or have a problem understanding English.

10. Ignoring student-to-student microaggressions, even when the interaction is not course related.

For more information, refer to a publication on Microaggressions in the Classroom from the University of Denver Center for Multicultural Excellence.

Example Classroom Scenarios

By watching these videos, we hope that you will understand what microaggressions are and how they manifest themselves in the classroom, and through discussion with colleagues and additional reading, learn best practices in effectively addressing microaggressions in the classroom contexts.

Classroom Microagression Scenarios 1-6

Scenario 1 – Age

Scenario 2 – Disability

Scenario 3 – Ethnicity

Scenario 4 – Gender

Scenario 5 – Gender Identity

Scenario 6 – Invisible Physical Disability

Classroom Microagression Scenarios 7-12

Scenario 7 – Linguistic Diversity

Scenario 8 – Race

Scenario 9 – Religion

Scenario 10 – Sexual Orientation

Scenario 11 – Socioeconomic Status

Scenario 12 – Veteran

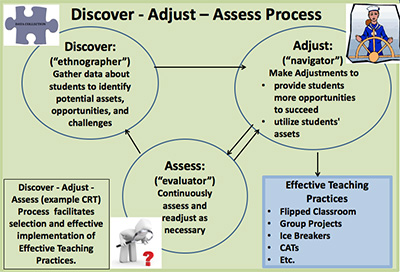

What is CRT?

Culturally responsive teaching (CRT) is a research-based approach to teaching. It connects students’ cultures, languages, and life experiences with what they learn in school. CRT focuses on the assets students bring to the classroom rather than what students can’t do while raising expectations and making learning relevant for all students.

In this captivating video set, Professor Alla Webb and Professor Ray Gonzales delve into the transformative approach of Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) as a powerful method to foster student engagement and facilitate meaningful learning experiences.

To explore further insights and information about Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT), click on the following links. Gain valuable insights and access to resources that will further enhance your understanding of CRT and its potential for creating inclusive and empowering learning environments.

What does decolonizing the curriculum mean?

Decolonization is “the process of deconstructing colonial ideologies of the superiority and privilege of Western thought and approaches. Decolonization involves valuing and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge and approaches and weeding out Western biases or assumptions that have impacted Indigenous ways of being” (Cull et al., 2018, p. 7).

Decolonizing the curriculum should also address the materials used in the course. This process involves “expanding our notions of good literature so it doesn’t always elevate one voice, one experience, and one way of being in the world. It is about considering how different frameworks, traditions and knowledge projects can inform each other, how multiple voices can be heard, and how new perspectives emerge from mutual learning” (Keele, n.d.).

Why is it important to decolonize the curriculum?

- Decolonizing the curriculum involves recognizing one’s positionality. According to dictionary.com, positionality is “the social and political context that creates your identity in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability status. Positionality also describes how your identity influences, and potentially biases, your understanding of and outlook on the world.” When instructors understand their positionality, they can consider how their identity and experiences impact learner success.

- Decolonizing the curriculum is a matter of social justice as it promotes an inclusive environment that respects all learners and their backgrounds.

What does decolonizing the curriculum look like in practice?

Mullings (2019) offers four recommendations for how to practice decolonization:

- Sit among your students. This means reconfiguring the learning space so that the instructor isn’t always front and center lecturing to students.

- Ask for student participation at every step. Inviting students to give feedback and take an active role in the learning process, and they become co-creators who contribute to the content, assessments, and activities.

- Demonstrate that you are not the only knowledge-holder in the room. Decolonizing means inviting students to contribute their knowledge and expertise and serve as co-creators of knowledge.

- Facilitate, guide, and coach throughout the room. This approach promotes student-centered learning and a two-way communication process that empowers students to take ownership of their learning.

References

- Cull, I., Hancock, R. L. A., McKeown, S., Pidgeon, M. & Vedan, A. (2018). Pulling together: A guide for front-line staff, student services, and advisors. Victoria, BC: BC campus. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfrontlineworkers/

- Keele University. (n.d.). Keele’s manifesto for decolonizing the curriculum. https://www.keele.ac.uk/equalitydiversity/equalityframeworksandactivities/equalityawardsandreports/equalityawards/raceequalitycharter/keeledecolonisingthecurriculumnetwork/#keele-manifesto-for-decolonising-the-curriculum.

- Mullings, D. (2019, Oct. 4). Decolonizing post-secondary classrooms for rockstar learners. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/SW0chDCifPQ

In fall 2022, a group of faculty, staff, and students at MC formed the Decolonizing Community of Practice. The following list of books was compiled based on recommendations and research by members of the community of practice. If you’d like to use the books as resources for teaching and learning, consult an MC librarian as some titles may be accessible online.

- Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Becoming Kin: Am Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future by Patty Krawec

- Our Knowledge Is Not Primitive: Decolonizing Botanical Anishinaabe Teachings by Wendy Makoons Geniusz

- Unsettled Expectations: Uncertainty, Land and Settler Decolonization by Eva Mackey

- True Reconciliation: How to be a Force for Change by Jody Wilson-Raybould

- An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the US by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

- There There by Tommy Orange

- MC Library offers a research guide with supplemental material for this book: https://libguides.montgomerycollege.edu/c.php?g=340991&p=9823931

- This title was selected as the 2023 One Maryland One Book program. For more information, see the Maryland Humanities Council website: https://www.mdhumanities.org/programs/one-maryland-one-book/

In the Podcast ‘Diversity of Diversity’, Fons Trompenaars is interviewed with the CEO of the Aegis Group.

Insights about Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DIE) are put in the context of leadership, systems, generations, and the benefits or business case in creating a culture of DEI.

The following main points are shared:

- Diversity starts with leadership.

- Organizations and their leaders must recognize the need to act if they want to create a diverse and inclusive workplace.

- The diversity of a system needs to be at least as big as the diversity of its environment

Otherwise, the system will die.

- Great leaders can be found at every level in a company.

- Different leadership generations face different issues, and leaders need to constantly act on new emerging challenges.

The point is made that diversity of opinion is not what DEI should focus on, and a main of leaders is to stimulate DEI dialogue and seek authentic change.

Click here to listen to the full episode: https://buff.ly/3uhXslV

Positionality and Positionality Statements in Teaching

Jackie Broussard (2022), writing for Verto Education, defines positionality as “where we stand in relation to dynamics of power and privilege” (para. 2). She continues and claims that positionality is also the set of identities we possess, such as race, class, gender, and religion, and how these identities influence and color our views (Broussard, 2022).

Broussard writes from the perspective of a college student preparing for a semester abroad, advocating that students should be aware of their positionality before they travel and engage with other peoples and cultures. “A crucial part of becoming a global citizen is being self-aware and cognizant of the effect our presence has on our environment” (Broussard, 2022, para. 3).

Positionality has become an important consideration in the world of research in recent years. Jacobson and Mustafa (2019) write, “The way that we as researchers view and interpret our social worlds is impacted by where, when, and how we are socially located and in what society” (p. 1). It is recognized “that the way that researchers perceive the social world is largely dependent on their position within it” (Jacobson & Mustafa, 2019, p. 2). Like college students preparing to go abroad, responsible researchers become cognizant of their positionality, which can also be seen as an aspect of global citizenship. Read more…

Two important components of inclusive language in the classroom and in the workplace include pronouns and names. When we use inclusive language, we are proactively acknowledging people and showing respect for their identities.

Pronouns

Pronouns are small words that can have a very big impact. They are not just the stuff of grammar textbooks and language courses—pronouns are a key part of how we communicate gender expression and gender identity. An easy way to make introductions more inclusive, whether in a classroom or a team meeting, is to proactively share your own pronouns when you share your name. This demonstrates that it is a safe environment for others to share their pronouns as well. Note, however, that nobody should be forced to share their pronouns if they are uncomfortable doing so.

How do I share my pronouns with others?

A standard template to follow is “My name is Firstname Lastname. My pronouns are ___/____/___”.

People usually share pronouns in twos or threes. For example, “she/her/hers,” “they/them/theirs,” or “he/him.” However, there are many pronouns beyond she, they, and he. Refer to the resources section below for additional examples.

How do I know what pronouns to use to address someone else?

A simple way to ensure you are using the correct pronouns to refer to someone is to politely ask them what their preferred pronouns are. Do not assume that you know someone’s pronouns simply by looking at them or by guessing based on their name. Refer to the resources below for additional pronoun etiquette tips.

Pronoun Resources

Why Pronouns Matter from the National Education Association

How Do I Use Personal Pronouns? from Pronouns.org

Pronoun Etiquette Tips from Carleton University Gender & Sexuality Center

SafeZone Trainings at Montgomery College

Name Pronunciation and Diversity

A person’s name is a fundamental part of their identity, and calling someone by their name is a powerful way to demonstrate respect for that person. Because there are almost as many different names as there are people in the world, it can be difficult to know how to pronounce names just by reading them on a roster or name tag. Similarly, not everyone goes by their first name or the name(s) that are listed in a database. When someone uses a name other than what appears on their official documents, this is called a chosen name.

Here are some simple tips to avoid awkwardly mispronouncing someone’s name or calling them by a name they do not use:

- Lead by Example

When you introduce yourself, say your name slowly and clearly. It can be helpful to clarify the parts of your name as well, since name order varies in different cultures. For example, you could say, “My name is Firstname Lastname. My first name is Firstname. My last name is Lastname.” This helps the people who are meeting you know how to pronounce your name and models how they can help you learn to pronounce their names as well.

- Listen and Repeat

When someone introduces themself to you, listen closely to how they pronounce their name, and do your best to repeat it. If you are not sure, ask them if you got it right. It’s ok if you don’t quite get it the first time— practice is your friend.

- Avoid Reading Before Listening

If you are checking attendance for a class or meeting, avoid calling names off a list or roster. Instead, go around and ask people to introduce themselves so you can find them on your list. This is a great time to also incorporate pronouns and chosen names.

For example, someone might say, “My name is Alexader Gomez. You can call me Alex. My pronouns are they/them.” Having people say their own names first not only helps you learn how to pronounce their names correctly but also avoids inadvertently using the wrong name (for example, if someone’s name has not yet been updated in a computer system after a name change, or if they prefer to use their middle name, etc.)

- Familiarize Yourself with Diverse Names

Get to know the backgrounds of your students and colleagues and learn what names are common in their countries and cultures. For example, if you work with lots of Vietnamese and Ethiopian students, your examples might include a Ms. Nguyen and a Mr. Tsegaye. This familiarity will also help you to more easily pronounce and spell students’ names correctly.

As you get to know the demographics of the people you are working with, you can respectfully incorporate representative names into your materials in lieu of hypothetical characters— Joe Schmoe and Jane Doe are ready to retire!

Name Resources

Understanding the Importance of Name Pronunciation from inclusiveemployers.co.uk

Most Common Last Names by Country from NetCredit

An inclusive syllabus uses language that fosters a welcoming and inclusive classroom environment and includes flexible policies and resources to support students’ learning. Instructors who embrace an attitude of empathy, understanding, and flexibility with students right from the start provide a more vital path to their success.

How can we begin by creating an inviting and inclusive classroom culture through the syllabus?

Instructors have the power to determine the approach and the tone of their syllabus. By communicating in ways mindful of their student audience, instructors establish a classroom culture of mutual respect and trust.

What do we mean by universal design for learning (UDL)?

UDL is a framework that offers a powerful approach to assist instructors in anticipating and planning for all learners from the very start. Course planning is inclusive when it embraces learner variability. Through the UDL framework, an inclusive course design captures the greatest range of students to access and engage in meaningful learning by removing barriers to their learning.

Kirsten Helmer, Director of Programming for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion with the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at the University of Massachusetts, contributed a chapter on “Six Principles of an Inclusive Syllabus Design” to the book “Equity and Inclusion in Higher Education: Strategies for Teaching,” (Helmer Recognized for Writing on Creating an Inclusive Syllabus, 2022)

The Six Principles

These six intersecting principles of an inclusive syllabus offer a scaffolding framework for the gradual (re)design of a traditional syllabus.

- Shift from content- focused to learning- focused.

- Organize your syllabus around Big Questions and Themes

- Create a syllabus that reflects UDL principles.

- Rework your language to demonstrate inclusiveness.

- Re-frame course policies to optimize students’ motivation and facilitate personal coping skills.

- Design your syllabus with accessibility in mind.

Create a syllabus that reflects UDL principles. |

|

|